Kenya and “the decline of the world’s greatest coffee” – Christopher Feran

December 25, 2021

17 minute read

The sun never sets on the British empire.

attributed to John Wilson, 1829

During one of his “yes or no” Instagram Q&As, Scott Rao lamented the declining quality of Kenyan coffees over the last three years—a sentiment I’ve heard echoed by buyers across Europe, the US, and Australia. He kicked a different question over to me about whether cultivar or microclimate or process has the greatest cup impact, and I demurred, offering that the relationship is gestalt but that processing ultimately had the final say —invoking Kenya’s declining cup quality as an example.

In our DMs, I shared with Scott my theory about the cause of this phenomenon—and noted that it was connected to some of the challenges of working there as a coffee buyer. He suggested I write a blog about it—a suggestion that I got from more than a dozen of my followers later that night.

So here it is.

Kenyan coffee holds a special place in the hearts and minds of specialty coffee buyers and roasters. Coffees from Kenya are prized for their physical density, long shelf life, vibrant acidity, intense cup profile, and often, distinctive aromatics like currant (or tomato—depending who you ask).

I’ve written about the most memorable coffee I’ve ever cupped—the one that got away. It was a Kenyan.

The most common theory explaining the apparent decline in quality of Kenyan coffees rests the blame with an increase in Ruiru 11 and Batian in the lots (and, concurrently, a decline in SL-28 and SL-34). I’ve written about that too (about halfway through) and don’t buy that argument.

And besides—looking at the export lots available from many of the more famous estates and associations, as well as African Taste of Harvest winners—it’s clear that many (if not most) contain at least some of these hybrids.

I don’t buy it.

Kenya is a tricky place to work as a buyer.

While in some origins, a smallholder would be able to grow and process their coffee as they please and then have a choice to either sell that parchment or dried cherry to any exporter in the country for immediate payment—or even secure their own export license and self-export—producers in Kenya are removed from the commercial market, their coffee passing through a Byzantine and colonial export system that centralizes sales through an auction system with exporters in the position of greatest power, sacrificing traceability and financial transparency along the way.

It means we can’t work directly—not really, anyway—and have to navigate through the labyrinth of the auction system to secure the coffees we want, all the while wondering where the $5 or $6 or $7 per pound we’re paying is really going.

Coffee wasn’t something that was native to Kenya or even traditionally grown there—even as Kenya shares a border with Uganda (home of robusta) and Ethiopia (the birthplace of Arabica). Though first introduced to Kenya in 1893 by John Paterson on behalf of the Scottish Mission from seeds obtained from the British East India Company, the completion of the Ugandan Railway and arrival of European settlers ultimately led to the introduction of plantation agriculture and large-scale cultivation of cash crops like tea, wheat, sisal—and coffee. As a colony of the British crown, the settlers were tasked with paying for construction of the railway and the export of coffee was expanded rapidly to settle the debt.

By 1912, Kiambu-Kikuyu boasted plantations several hundred acres in size.

Of the larger export companies still operating in Kenya, many have their roots in the colonial period, such as Dorman’s, which was founded in the 1950s, and Taylor Winch in the 1960s. I’ll never forget the first time I walked into the offices of these two companies and noted that the managers and people in charge were all white—either Europeans or white, Kenyan-born descendents of British settlers—and everyone cleaning up the cupping table when we were done was an indigenous Kenyan person (one of the bosses of one of the companies—a white man, of course—was even wearing a khaki safari shirt. You just can’t make this shit up).

Within hours of arriving in Nairobi for the first time, it was clear to me that coffee in Kenya still largely operated as an extractive, neo-colonialist enterprise.

In Kenya, if a producer has less than 5 acres, they legally need a coop or society to process and market their coffees. Historically, around 30% of coffee in Kenya comes from estates, with the remainder coming from some 400+ cooperative societies—but in recent years that number has shifted to 45% from Kenya’s roughly 24,000 estates and the remainder from around 85,000 smallholders (according to the Kenya Coffee Traders Association’s Kenya Coffee Directory).

The best co-ops might have financing available to producers as well as traceability and receipt systems in place to maintain some transparency as coffee passes through the export system. The societies own and operate the washing stations (there called factories) where their members’ coffee is processed (according to the export standards in the country, all export coffee must be washed).

After coffee has been fermented, washed and dried, movement permits are pulled (a legal requirement to transport coffee anywhere in the country) and it’s sent to one of the country’s eight mills, which is paid to remove the husk and sort the coffee to prepare for sale through the auction or an exporter.

In Kenya, though, millers cannot export themselves; coffee must pass through a “marketing agent” to make the sale to an exporter — a bonus middleman special to Kenya’s system.

The miller selects and hires the marketing agent, which is, in practice, very often one and the same entity. This system is lubricated through bribery: marketing agents pay allowance to board members of societies to get them to agree to market their coffee through that agent, which in turn affiliates them with an exporter. (It’s likely illegal, and some marketing agents such as Coffee Management Services/Dorman’s insist they don’t engage in the practice).

From there, the marketing agent markets the coffee on behalf of the society and miller to exporters to earn their 1.76-3% commission.

In Kenya, though, the coffee remains the property of the society until its final sale through auction or export, with fees deducted along the way. The remainder is paid to the society, which in turn takes its own cut and pays out the farmers.

In effect, this means that a farmer whose coffee was harvested and processed in October and exported in March would not get paid until March or April—some six months later, and well into the flowering period for main crop. Any nutrients, amendments, fertilizers, or pesticides the farmer needs—let alone the costs of food, housing and living for themselves or their families—would need to be financed for that 6 month period prior to final payment from the exporter to the society and from the society to the farmer.

Commercial financing rates for coffee producers in Kenya are higher than 20%, effectively making them agricultural payday loans. Co-ops often offer lower rates—but still higher than 10%. These financing costs compound the actual cost of production for smallholders and diminish their profits once that final sale is complete.

And if a miller isn’t honest or reputable, out turns from the mill may be low—80% is quite common—lowering yields and driving up costs to the grower even further—and creating an opportunity for the miller’s pocket to be lined (which is the most fucking colonial British thing ever—it sort of reminds me of Elizabethan England where you’d tip your executioner to ensure they did good, clean work and removed your head in one swing).

In order to improve the speed of payment, a society could do its own milling (for example, if they’re larger or a union member with access to resources) by building a mill or reactivating an unused mill at which point a society could get a grower/marketing license (likely while paying absurdly high interest rates on the capital they invested to build the mill)—however, according to the Kenya Coffee Directory, only 9 of these licenses have been issued.

But even then—the society still can’t export; they just control their own milling and keep that process control and the fee that would otherwise pass to a third party.

Most of the coffee that flows through auction system comes from as few as eight marketing agents, four of which are vertically-integrated and owned by subsidiaries of the major export players (like CMS which is owned by Dorman’s, Tropical which is owned by Neumann Group, and SMS which is owned by ECOM).

In total, at the time of my last visit to Kenya in 2016 there were just 45 export licenses for coffee in the entire country. The amount of money passed between entities to establish blocks of power in otherwise competing businesses is otherwise pretty staggering—money passing from one hand to the other in a scheme that effectively fixes prices paid to producers across the country and limits the ability of producers to sell their coffee freely in a competitive market.

For example, Dorman’s, which was founded in 1950 and is the oldest exporter in Kenya, used to be a part of Taylor Winch and ED&F Man. It’s now independent, or so it says—but ECOM is its shareholder and financier in spite of the fact that ECOM has its own export license and separate marketing agent pipeline.

No matter which demon you sell to, it all ends up in the devil’s pocket.

Dorman’s supplies coffee to many of the most famous third wave roasters in the world (I once got kicked out of a Dorman’s cupping because a certain Scandinavian guest of honor arrived and wanted a chance to cup the coffees first) and offers certain advantages to societies that hire CMS to market their coffees.

By selling cherry through Dorman’s, producers get access to loans and pre-financing below commercial rates, as well as training on good agricultural practices and assistance getting certifications. Dorman’s extends these benefits as a way to access producers directly rather than having them sell to societies, though roughly 30% of all coffee that Dorman’s exports comes through cooperatives.

Dorman’s might pay a society something in the realm of 85 shillings per kilo of cherry, or around $0.75-0.80 USD per kg—significantly higher than the country average of 65 shillings per kilo ($0.57-0.60).

On the high end this translates, roughly, to the equivalent of around $1.85 per pound of green coffee—a pretty good price, to be sure—though it pales in comparison with the $5-7 per pound most roasters are used to paying for Kenyan coffee.

But the average price paid to producers for cherry translates roughly to $1.42 per pound.

The best coops, where premiums of 85 shillings per kg are paid, might retain 5% of the sale, but it’s extremely common for coops to retain roughly 20% from the sale, leaving, in the typical case, just $1.13 per pound to a producer—well below their costs of production, even before the marketing agent’s 3%, or milling fees (roughly $70 per metric ton), or out turns, or financing costs that float a producer between harvests.

Seriously: Why bother?

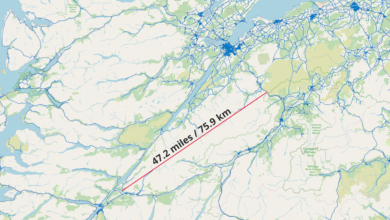

About 25 years ago, Kenya’s coffee production was about triple what it is today. Some of that has to do with politics—the second president of Kenya, Daniel arap Moi, took away the support system for coffee as a mechanism to suppress opposition—some has to do with competing exports (like tea) being more lucrative or liquid, but largely, urban sprawl consumed lands used for coffee cultivation as Nairobi exploded in population from just 850,000 in 1980 to nearly 5 million in 2021:

Kenya’s acreage under coffee production has decreased by over 30 percent from about 170,000 hectares in early 1990s to about 119,000 hectare in 2020. The production of the cash crop has also decreased by a whopping 70 percent from a peak of 129,000 metric tons in 1983-84 coffee year to about 40,000 metric tons currently.

[source]

Why bother, indeed: why grow coffee when you can make a better living by selling your land?

But that’s a problem: declining production means declining efficiency, and most of the factories in Kenya were built to accommodate massive volume.

Until recent reforms in 2021, the style and process of coffee was dictated to producers, limiting their ability to refine processes as volumes fluctuated or account for new techniques, technologies, or the evolving tastes of buyers (as I understand it, it was illegal until recently to export natural processed Kenyan coffees for this reason).

At peak production, Kenyan factories faced issues and bottlenecks familiar to many coffee producers around the world—most often as it entered the phase of processing requiring the most space and time: drying. Even if conditions were right and if the coffee were dried in full sun, it could take 7-9 days for coffee to dry enough to move into storage. To break down pulp in a dry fermentation—as is the standard in Kenya—it might only take 12-20 hours.

This means that as cherry was received, it would pile up, awaiting drying. It’s kind of like when you’re try to do three loads of laundry in a side-by-side washer and drier: the wash cycle might only take 30-35 minutes but the drier might take an hour. You have to wait for the drier to finish before you can move your clothes over and begin the next cycle. But if you wait too long—the clothes (the cherry) will rot.

So what do you do?

You could build more space for drying—or you could engineer workarounds to elongate the first part of the process to synchronize when coffee exits drying and more coffee enters, in essence creating a buffer for drying space.

In Kenya, this meant the introduction of the “double washed” or “double fermented” style of coffee many buyers are familiar with. Coffee would be fermented dry for 12-24 hours, washed, and then sent to a holding tank where it would be soaked in clean, cool water for up to an additional 24 hours or longer (the so-called “secondary fermentation”). In some mills, after the initial 12-24 hour dry fermentation and washing, a second dry fermentation would occur before soaking. A single pass through the fermentation step, though — ferment, wash, soak — could theoretically extend the amount of time that coffee could hang out before drying by a day or two, enough time to delay sending the coffee to dry and allowing the factory to make space on drying tables.

One thing Lucia Solis and I have long disagreed about is the necessity or efficacy of the “second fermentation” in Kenyan style washed processes. Lucia argues that it’s inefficient, creating an additional step and prolonging the processing time and therefore unnecessarily increasing costs. She believes the same flavor profile could be generated using other techniques.

I counter that it was a technique that was, in fact, introduced to engineer a solution to capacity issues and therefore is efficient because it requires no additional infrastructure — merely idle time. Further, I believe there is merit to the notion that the soak functions as a “secondary fermentation” (though really it should be called a “sequential” fermentation process) producing a flavor profile that would be more difficult and riskier to achieve in a less time-intensive manner.

Coffee fermentations are, as I’ve discussed in the past, mixed microbial fermentations involving “the activity of a wide range of microorganisms such as yeasts, lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), spore-forming bacteria, and molds.” (Masoud et al. 2004; Schwan and Wheals 2004; Nielsen et al. 2007, 2013). Typically, over the course of a coffee fermentation, the population dominant in the tank will modulate based on the environmental temperature, pH of the fermentation, availability of oxygen and nutrient, fermentable sugar concentration, and finally, ethanol content.

While yeast is associated with degradation of the pectins in coffee mucilage, bacteria such as LAB and AAB are associated with the production of acids (Ruta,L.L.; Farcasanu,I.C. Coffee and Yeasts: From Flavor to Biotechnology. Fermentation 2021, 7, 9). The specific fermentation kinetics dictate the microbial succession as different microbes will be better adapted for certain conditions at different times during the fermentation. At the onset of fermentation, lactic acid bacteria and yeast may grow in tandem, with LAB having a briefer (or no) lag phase and therefore producing metabolites before yeast has established. However, as a byproduct, in addition to lactic acid (which lowers the pH in the fermentation tank) LAB may produce—or enable production from other microorganisms—compounds that are toxic to LAB, leading the bacteria to die off or stagnate. Yeast, however, are more robust and would continue to ferment and replicate, and by virtue of their metabolism, continue to break down sugar and produce alcohol, carbon dioxide and (under ideal conditions) secondary metabolites.

This daisy chain of microbial activity creates a situation where the pH in the tank has dropped (probably to between 5-6), the moisture level has increased (as water is liberated from the disintegrating mucilage), there is quite a bit of ethanol (because of the yeast), and there is plenty of oxygen in the environment (because these fermentations are conducted uncovered and in ambient air). This is the most favorable set of conditions for the replication of AAB. Whether or not LAB continues its own metabolism, left unchecked, AAB will replicate and produce vinegar—rendering the resulting coffee defective.

But Kenyan processors introduced an extra step to interrupt this cycle halfway through—they washed the coffee (stripping away most of the food source for our fermenters, as well as the acids hanging out loose in the tank) and added fresh water (diluting the concentration of sugars thus inhibiting LAB and yeasts, decreasing availability of oxygen, and raising the pH). The temperature of the water is also cooler than that of the previous fermentation—and as we know from basic biology, lower temperatures result in slower metabolism of microorganisms (this is one of the main reasons that fridges help to stop spoilage).

All of this means that Kenyan coffee producers were able to extend the time that coffee sat in the tank prior to drying without risking spoilage—solving the issue of needing to make the wash cycle last long enough to wait for the previous load of laundry to come out of the drier.

But there was an unexpected benefit: as the washed, previously-fermented coffee sat in the tank, it was still microbially charged. Yeast like Saccharomyces Cerevisiae—a facultative anaerobe—would continue to replicate and produce alcohol underwater (though initially slower than before). With oxygen still readily available (whether dissolved in the water or through cellular oxygen), pH once again between 5-6 in the interstitial liquid, and with abundant ethanol from the previous and continuing fermentation, AAB once again kicked into gear and produced vinegar. Because it had to build population again, the initial rate of this production, though, would be low; and the water the coffee soaked in would mix with the vinegar produced by AAB and dilute it, meaning that the coffee would not spoil but would absorb just a small concentration of acetic acid from this production, while the other metabolites from the prior, dry fermentation redistributed and homogenized in the lot.

In low concentrations, humans perceive acetic acid as “fruity” or “floral” as well as quite sour. And in coffee, acetic acid is the only volatile organic acid present—helping to draw other volatile compounds in coffee toward the cupper and heightening the aromatic intensity of the coffee.

Much like the “signature” Kenyan profile.

But we’re not done: After the soak, the coffee would be put on raised beds in the sun in a thin layer to rapidly dry the surface water in a “pre dry” stage. This could very quickly—within a day or two—get the coffee down to ~45% moisture, accelerating the wet coffee through the most precarious stage of drying. The coffee would then be moved to the drying stage.

If there was not room on the drying beds, though, coffee that was partially dried—down to 20-24%—could be moved to a “holding pen” for up to several days—allowing the previous batch the opportunity to finish drying completely, and creating room on the skin drying tables for any incoming coffee exiting the soaking tanks.

While this “holding” of partially dried coffee would have less of an impact on quality per se (though microbial activity would continue at a lower level, and likely modulate toward filamentous fungi and yeasts) it would create an opportunity for intracellular moisture in the coffee—which was abundant due to soaking, but unevenly distributed due to the pre-drying step—to redistribute and homogenize before the coffee completed drying. The benefits of interrupted or intermittent drying or resting periods during drying have been well established—and this additional rest would, additionally, help to preserve and protect the coffee from fade by helping the coffee dry more uniformly after resting.

Over the last four years, I’ve noticed a change in the character of the coffees from the coops I bought from—coops of whose coffee I’ve been cupping since 2013 or 2014 and thought I knew quite well. The mix of cultivars hadn’t changed, and they were being processed at the same factories and mills and through the same marketing agents and exporters as before.

But a couple things had changed: their volume of exports had slowly decreased, and the premiums we’d paid toward improving the infrastructure at the factories, as far as we could tell, had not actually resulted in those improvements being made.

I noted that some changes were made to the way the coffee was processed. Because drying space was no longer in short supply—except perhaps for a short while at peak harvest—the holding pens weren’t in use anymore. The coffee went on the beds and stayed there. And of course, because in Kenya’s export system a coffee must first pass through a dry mill before auction and export, this means that unlike other countries—where coffee can be stored in parchment to homogenize or stabilize prior to final sale, it’s removed from its protective layer months before shipping and stored in warehouses without climate control dotting Nairobi.

If it doesn’t stabilize during drying—like in a holding pen—it would be more susceptible to fade, a phenomenon I have observed in the samples I’d tasted and Kenyan coffees I’d hoped to enjoy from other roasters.

And then there was the fermentation: the factories I bought from no longer practiced Kenya’s signature “secondary fermentation” or soak—and they insisted that they weren’t the only ones who’d given up the practice. I looked around, and—they were right.

All of those extra steps—an extra day or two in the tanks, an extra 4-5 days in drying—amount to extra costs.

And it’s not like the producers were getting paid more for the coffee, so—why bother?

At the dry mill, we faced similar volume-based conundrums. While lot sizes passing to auction might be anywhere from 1-100 bags, it was common for smaller lots to be aggregated into larger ones simply as a matter of cost efficiency. There’s “changeover” loss when mills switch between distinct lots—there’s coffee retained in the system as well as recalibrations that need to be performed. With larger mills—like those in Kenya and those that were endemic to Colombia until the last decade—the amount of loss was greater. This means that they perform more efficiently as larger lots pass through them.

Think of it like a coffee grinder: if your grinder retains or exchanges 2.3g of coffee every time you grind and your dose is 20g, every time you grind coffee you’re theoretically losing about 11% or adulterating the coffee you’re grinding with 11% of previous batches. But if you’re grinding 500g, loss or interjection of 2.3g is just 0.46%—hardly likely to have any significant impact on your cup, and acceptable levels of loss.

So if these mills need more coffee passing through them to create the Kenyan coffee we remember—and coffee production is in decline—what now?

I’m pretty ambivalent about the notion of trying to buy coffee from any certain place, especially for something as increasingly available as quality. Every export system in the world functions with its own set of rules and challenges and possibilities. But Kenya’s challenges are decidedly in a class of their own.

I stopped working there not because I don’t love the coffee or think it’s too expensive—but because it’s too opaque, too indirect, too diffuse.

It’s impossible to develop an equitable relationship when it’s systematically, legally set up to be an extractive one.

Many of the quality challenges, I think, can be solved through appropriate economic and fiduciary mechanisms and policies. Further, small scale mills and micro mills like those in Colombia and those we’re starting to see in Ethiopia would help producers differentiate their own products as well as establish a level of traceability and separation not accessible through the current system. And liberalization efforts, like the proposed Coffee Bill 2021 under consideration by the parliament would reform many of the most egregious oversights that de facto legalize systemic corruption and the exploitation of producers today.

Ultimately, unless we can find ways to put more money in the hands of individual smallholders—by paying producers when an exporter takes custody, for example, and implementing financing mechanisms for producers at sustainably low interest rates, the question I asked at the outset still remains.

Why bother?

Stephen Vick—if you’re reading this—you’re perhaps the person best positioned to issue a rebuttal and/or inspire hope. Update: see comments for Stephen’s take.

[UPDATE 05 Jan 2022]

A few days after I published this post, Philip Magowan, a PhD candidate at University of Cambridge reached out. His research focus is on the coffee production in Kenya during the colonial period, and reading through his (unpublished) dissertation, the historical record establishes that the inequity in Kenya’s coffee production and export system is calculated, intentional, systemic and institutional in nature.

I look forward to linking to the dissertation when it’s published, but for now will leave you with a few paragraphs from his email:

As you may well know – British settlers sought to exclude Kenyan farmers from coffee production (and until the 1950s, they had largely succeeded in doing so). My MPhil thesis research investigated the role of quality in Kenya’s coffee production. I looked at how settlers used European ideas of quality-oriented coffee production to sustain the exclusion of Kenyans from coffee farming. The settlers established exclusionary coffee research facilities, credit services and even ensured that new railroads only serviced settler areas of coffee production.

In particular relation to your blog, when in the 1940s, the colonial government were discussing how the first Kenyan-produced coffee crops should be processed and marketed – the settler farmers proposed that coffee from the Kenyan smallholders should be processed together in larger consignments that ignored any distinction between individual farmers’ lots. In comparison, each settler estate was marketed in sacks marked with the name of the estate, and was processed as an individual lot. This process negated any value of an individual Kenyan smallholder’s efforts, and further disincentivised farmers from working to increase the quality of their coffee. As you have highlighted for the similar issue arising today – why bother?

Indeed, one of Kenya’s agricultural officials at the time, trying to explain to the Kenya govt why these rules were unjust, noted ‘By pooling the lots into one consignment, the quality of the greatest farmer’s coffee is rendered no better than that of the worst; like a fleet of ships, progress of the whole is tied to the slowest vessel.’ It is interesting that a similar issue arises today, where to save money lots are processed together, though at the ultimate expense of quality.

When writing my thesis, some of the conclusions that you came to in your blog were also apparent to me. The institutional legacy of the coffee marketing structure in the colonial period has chronically pervaded the prevailing structures today. I have never felt like I understood the contemporary industry well enough to comment, but a rewrite of these institutions from a government level does seem to be the only solution. Businesses like ACR are doing a fantastic job but the co-ops are now too significant a social/welfare role to vanish completely from the lives of coffee farmers.

Peter Magowan, ‘African Exclusion in the Quality-Oriented Coffee Industry of Colonial Kenya (c. 1893-1950)’ (unpublished MPhil Dissertation, University of Cambridge, 2020).

Tags: coffee fade green coffee kenya processing quality scott rao