In the Rockets’ Red Glare, by Rachel Kushner

Illustrations by Barry Falls. Source photographs courtesy the author

Listen to an audio version of this article.

When we got to southern Kentucky, we were nine months into our pursuit, an apprenticeship to a dreamworld that we had stumbled upon. I had just expressed my amusement to Remy that our new friend Paul Brown—we had so many new friends—was smoking a cigarette as he casually poured gas from a jug into the fuel tank of his golf cart, a standard pit vehicle at drag strips. People like Paul Brown who have decades of experience with dragsters know what real danger is, and so the humor here, as I saw it, was that minor forms of risk, like smoking while handling gasoline, were no big deal, little taunts at chaos that only reinforced an impression of control.

But a lit cigarette won’t actually ignite gasoline, Remy told me. It isn’t hot enough.

It’s still a flex, I said, and he allowed me that.

Remy and I had our private commentaries, always on alert for little ironies and epiphanies, as we seized on the richer details of what I just described to you as a dreamworld but isn’t. It is real, and we didn’t entirely stumble upon it. Because who, among Americans, would not have at least heard of drag racing? Would not be able to conjure some image, no matter how vague, of what it is? Our burst of interest pertained to one of its subgenres, even as we would come to consider it a supergenre, an urtext: nostalgia drag racing, a sport and pastime of people reprising twentieth-century technologies and stressing them to their absolute maximum.

In contemporary professional drag racing, where the technologies of speed have been refined to a single vanishing point, the cars all look the same. At the upper levels, the sport is corporate—there is a single way to get from A to B, deploying money, computers, ultramodern materials, physics, and fuels. But once upon a time, there were a hundred ways to get from A to B, or a thousand. There were dragsters with three wheels. Dragsters with two engines. The history of going fast in a straight line down a track has been, until recently, an extreme counterculture of people trying out bold and crazy experiments to denature and renature machines. Nostalgia racing celebrates this history by bringing it back to life. Vintage dragsters on the nostalgia circuit aren’t museum displays, dead spectacles of the golden era in chrome and candy flake. Instead, they are raced, torn down, rebuilt, and raced again.

Our first glimpse of all this had been at Famoso, a historic track nestled among almond orchards north of Bakersfield, California, where we watched the wheels of exotic vintage machines push at the Earth with such force as if to turn it. We had taken in the mood of the place, a folksiness blended with stunning violence, and pledged to move toward the heat and metal and noise.

Now it was June, and we were at the National Hot Rod Association’s Nostalgia Nationals at Beech Bend Raceway in Bowling Green, Kentucky. The weather was brutal, and it was forecast to remain so: sunny, low to mid-nineties, wiltingly humid. In the distance, an antique roller coaster creaked along wooden tracks, and I wondered who would choose to ride it when there were so many cars to ogle and races to watch and people to meet.

It was day two of the three-day NHRA event. We had just left Paul’s pit area with cold bottles of water that he’d given us, and this is what we looked like: a sixteen-year-old boy and a middle-aged woman, each some variety of redhead and likely related, sporting baseball hats and sunglasses and carrying protective earmuffs, coated in sweat but undefeated by the climate. The boy almost a man: thin, broad-shouldered, and at six feet, taller than the woman by several inches, the two of them moving along with purpose like they were some kind of team, conferring and comparing notes in matching purple-mesh media vests that said nhra in big white letters.

Remy was trying to help me understand vaporization, how it is that gas ignites. It needs heat, he said, and also surface area.

“So I could drop a lit cigarette into a gas can,” I ventured, “and it would just . . . go out?”

I pictured a gas can as I said this, red, of course—we call them cans but they’re plastic—like the ones Remy leaves here and there, in the garage, the basement, the toolshed. I phantom-smell gasoline from these containers and complain about it, but he says he doesn’t smell anything. And even if he did, he’d be unbothered, because he loves the smell of gas.

The cigarette would go out, he confirmed. Liquid gas, he said, wouldn’t actually catch fire. “As a rule, liquids themselves don’t burn. It’s their vapors that burn.”

Petroleum and its properties had become a focus of Remy’s—a hobby, even—ever since his Los Angeles public school shuttered for seventeen months in early 2020. He was twelve at the time, and suddenly academic instruction was minimal to nonexistent. He slept in, played the piano for long stretches, went fishing with my husband, and otherwise spent long hours online, pursuing a sudden and consuming interest in petroleum refinement and organic chemistry. We almost wondered if this new passion were his version of rebellion, or payback. He was the child of people immersed in art and literature—the “humanities”—and he wanted to tell us in intricate detail how diesel is made, and about various “fractions” of the distillation process. “I’m on a need-to-know basis,” I’d plead. But the idea that someone would not be hungry to understand the material world, the inhumanities and how they work, didn’t quite register. Who would go out of their way to remain ignorant in the face of an informative lecture on bunker oil?

But to appreciate what’s happening at a drag strip—what you are hearing and seeing, what all the different race classes are—it’s necessary to understand some basic properties of petroleum distillates, which Remy could explain to me. He impressed upon me how strange and incredible it was that nitromethane, burned by funny cars and Top Fuel dragsters, the two fastest classes of vehicle, is not a traditional fossil fuel but an industrially made “monopropellant” that is highly explosive, on account of its containing its own oxygen. When you burn it in an engine, it can produce ten to twenty times as much power as the equivalent amount of gasoline.

Nitro is produced by combining propane and nitric acid. It is often used in dry-cleaning solvents, and no one knows when, exactly, the first brave fool decided to try feeding this unpredictable compound into an internal-combustion engine. The Nazis apparently subsidized its use by Ferdinand Porsche in the Thirties, for land-speed and Grand Prix racing. Unaware of this history, the driver and hot-rodding innovator Vic Edelbrock reinvented the technology in 1949, when he poured it into a Ford flathead V-8 and beheld its violence (it melted the spark plugs and destroyed the motor). Once Edelbrock figured out how to modify his engine he began using nitro in secret to win races, blending it with orange oil to disguise its conspicuous smell. The huge yellow flames shooting from the exhaust ports of his dragster tipped off competitors that he was doing something different, and soon the news of nitro spread.

After Timothy McVeigh posed as an enthusiast and purchased three drums of nitro at an NHRA event in Texas—an ingredient in the bomb he used to blow up the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995—the Department of Homeland Security started overseeing the use of nitro at races. The NHRA enhanced its regulations, too, with security and ram-proof barriers around the fuel drums (physical shock can detonate nitro). By the end of each nostalgia event, a roped-off dumping ground will be deep with empty blue fifty-five-gallon barrels, a testament to the thousands of gallons of nitro that racers have pumped into their engines.

Running an engine on nitro is high-risk, high-reward: typical mechanical issues, like a faulty or loose wire failing to get spark to a cylinder head—minor problems that would normally mean an engine might run on seven cylinders instead of eight, a barely noticeable loss of power—can in this case result in calamity. If nitromethane goes into the combustion chamber and doesn’t ignite, liquid fuel has no place to go, and the engine will explode, ejecting shrapnel and engulfing a car and its driver in flames.

Catastrophe takes many forms, and fans are not always safe from it. I’d heard a story of a broken crankcase flying into a grandstand at Famoso and injuring a spectator, who nevertheless asked the driver to autograph the hunk of metal that had hit him. There have been much grislier outcomes. Front-engine dragsters have an axle differential that is situated right up between the driver’s legs. If the gears break their case, they can slice everything in their midst. There are rumors of drivers being castrated in this manner.

When racing legend “Big Daddy” Don Garlits’s transmission blew up back in 1970, he was luckier, and lost only the front part of his right foot. But the engine case flew into the stands and severed the arm of a teenage boy. The boy and Garlits were taken to the same hospital (as Garlits tells it, orderlies loaded him into the ambulance and tossed his foot in as an afterthought). A doctor who was flown in to try to reattach the foot decided, with Garlits’s encouragement, to focus on the kid, whose arm was successfully reattached. The following year, he worked on Garlits’s crew at the same event. In the wake of his injury, and the fatalities of so many drivers in accidents like his own, Garlits pioneered a rear-engine dragster. Many were certain that such a wacky design would fail, but now this configuration is standard, and front-engine dragsters, for all their bravura, are completely obsolete—except at nostalgia events, where they win championships.

Remy and I have a refrain, perhaps started by me, that among nostalgia participants, “there are no knuckleheads.” At NHRA events and in the wilder unsanctioned scene, people know what they are doing. They have to. The clutch of a nitro car, for instance, must be disassembled following each use: after only a few seconds, the clutch plates get so hot that they can fuse together. Top Fuel engines take so much wear in a single run that they must be entirely torn down and rebuilt after every pass on the quarter-mile track. Perhaps the severe consequence of error narrows the field of prospective nostalgia racers down to those with mastery. Nostalgia racing demands mastery. There is a purity to the demand: there is no money to be made. There is fun, and glory, but underneath these is a more inchoate drive, an ontological imperative, maybe, to play with fire.

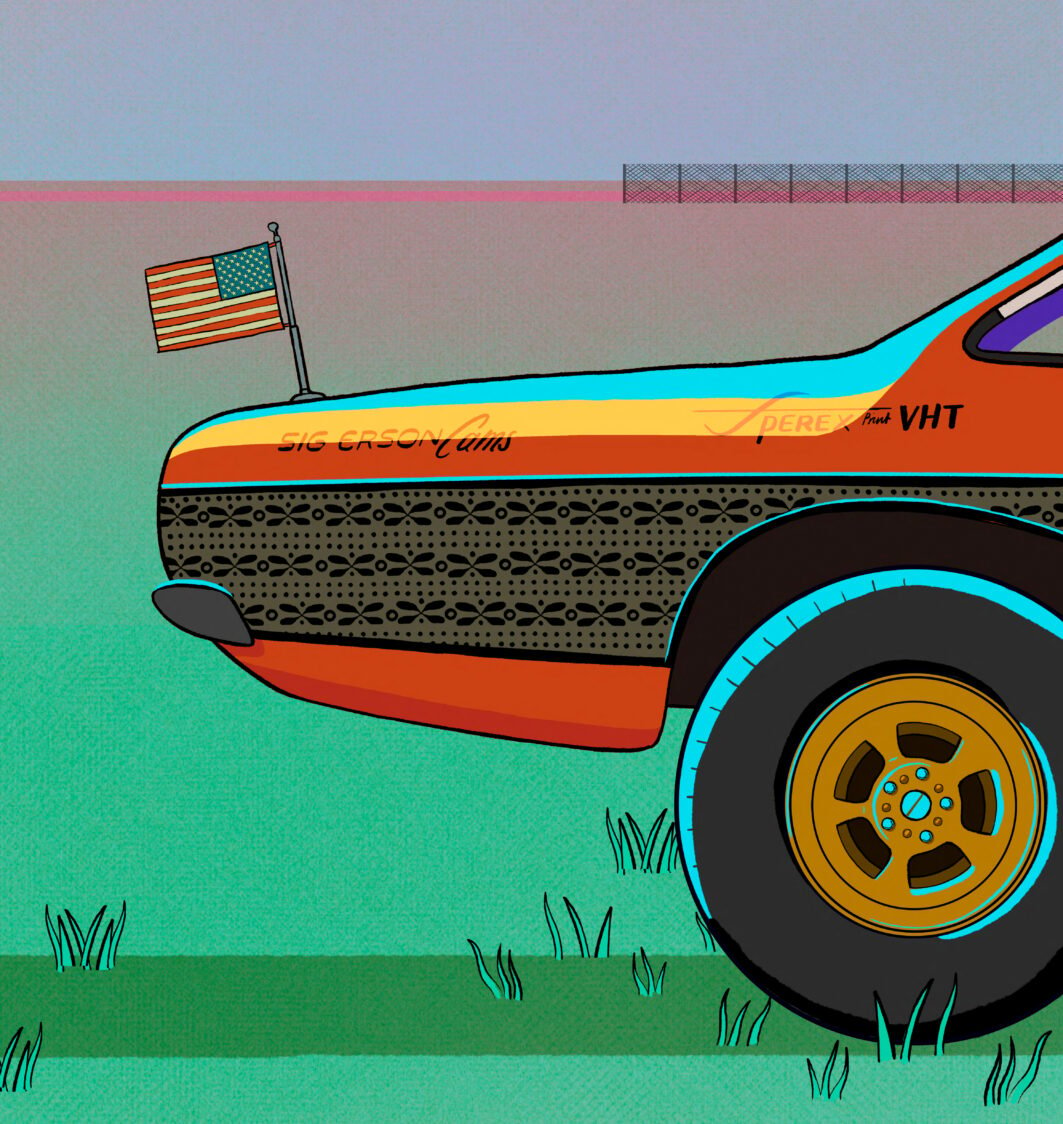

We first met Paul Brown when we’d stopped by his pit to talk to him about his vintage nitro funny car. For those unfamiliar with the specifics of drag racing: a funny car has a fiberglass body that replicates the look of a particular make and model, set over a chassis on which the driver sits behind an enormous engine. Paul’s car was a 1967 Chevrolet Corvair with a fantastically glossy candy-tangerine paint job and a black spiderweb detail. Originally owned by the celebrated racer Doug Thorley, the car had won the first-ever NHRA Nationals funny-car eliminator title, in 1967. Having acquired its original chassis, Paul painstakingly re-created it.

Paul is in his sixties but has a youthful and bohemian air, with a tall, lanky frame, a ponytail down his back, and the tattoos of past lives along the surface of his arms. He started off street-racing as a teenager, in Tucson, Arizona, but he gave it up after he almost hit a little girl on a tricycle. “It was so close,” he told us, shaking his head. He migrated to drag strips as a safer and more responsible way to go fast (drag racing was born as a way to take street racing off the streets). He raced until 1984, and then he quit, and got involved with a motorcycle club in Chicago. He found himself “a lot of trouble.” When his local club became a chapter of a syndicated and more notorious club, his wife, who was dying of cancer, asked that he not take their patch. This was her parting wish. Paul kept his promise. He remarried after she died, and now he was sober. This made sense: he had an air of abstention, of self-restraint, which his smoking habit did not contradict.

He had worked for his family’s faucet company and was now retired and doing what he loved: bringing the Corvair, and another Doug Thorley car, a 1964 Chevy Nova, to various nostalgia events around the country. He was planning to fire up the Corvair, he said, for the “cackle show” the next night. This would be the closing event of the Nostalgia Nationals, when they bring out the vintage Top Fuel dragsters and funny cars that cannot be raced because they no longer comply with modern safety rules. Instead, these still-ferocious vehicles would line up on the drag strip at dusk to be started and revved, their exhaust flames dramatic against the night sky. Spectators would watch from Beech Bend’s ancient wooden grandstands, safe from the stink and choke of nitromethane—and from the possibility of mishap.

“Want to be behind the wheel for the cackle event?” Paul asked me. It’s a crowd-pleaser, he said, and it’s fun for the media and the fans if someone unexpected gets into the driver’s seat.

The previous autumn, at Irwindale Speedway in southern California, Brant Inglis, a nostalgia-circuit mechanic from Arizona, had invited Remy to sit behind the wheel of his historic Top Fuel dragster for the cackle hour. For Remy this was an easy yes, and I hadn’t worried. I’d first met Brant at Famoso and had immediately liked him. Though he’s in his early thirties and baby-faced, he has the wise and capable air of someone much older.

I’d stood filming while Brant and his fiancée, Amber, started the car, “bottle-feeding” the engine methanol. (Nitro cars are started on gasoline or methanol, as nitromethane is famously inert until it is heated to a very high temperature.) Remy seemed stoic, but his face was hidden behind Brant’s fire mask, its interior cloth covered with signatures of famous drivers that Brant had collected over the years. Brant told me that when he wears the mask, he feels these legends’ protective spirit right up against his face.

When the engine was sufficiently warmed up, they switched it over to nitro. Watching the two of them tend so carefully to the car, with Remy behind the wheel, and hearing the phrase “bottle-feeding,” I felt, for a moment, that they were enacting some triangulated ceremony, almost like parents. (Amber is the granddaughter of a well-known drag racer, and her marriage to Brant would bind him directly to the legends whose autographs lined the fire mask.) Brant cracked the throttle. He and Amber grinned at each other. The car screamed a ragged series of explosive pops. Even with ear protection, the sound was apocalyptic, like the air itself was being torn to shreds. I lunged instinctively backward to get away.

By the time we got to Beech Bend and met Paul, Remy had sat in the driver’s compartment for a few of these starts. To him it wasn’t a big deal, but I felt hesitant about climbing behind a massive engine running nitro. I confessed to Paul that I was a bit scared. “Oh, you should be,” he said. “All it takes is a hung-up valve and things can go terribly wrong.” He described safety protocols and showed me what I would wear: a fire jacket and fire pants; fireproof hood and respirator; goggles, helmet, fire-resistant gloves; and fireproof boots. He assured me he’d be nearby with a large extinguisher at the ready.

Paul suggested a dress rehearsal. Figuring I could change my mind before tomorrow, I went to try on the jacket and pants in the narrow toilet stall in his trailer, while he and Remy got into an involved conversation about why nitromethane is so much denser than methanol, the two of them taking turns lifting five-gallon jugs of each. The ex-biker and the high school chemistry buff agreed: nitro is a heavier molecule than methanol. Remy confirmed with out-loud calculations of molar mass that nitro was almost twice as heavy as the methanol that would be used to start the funny car.

Meanwhile, the fire jacket, a satiny white that had yellowed with age, the name of some long-forgotten driver embroidered over the chest in blue, fit me perfectly, and so the choice seemed made that I would be wearing it tomorrow.

The same year that schools closed and Remy’s interests turned to petroleum refinement, my mother taught him how to drive her Subaru. The next year, my cousin taught him how to drive a tractor, a 1958 Oliver. When Remy was fifteen, my childhood friend Armand Croft, a lifelong gearhead and competitive off-road racer, let him drive a Rover Mini Cooper 1.3i and an Alfa Romeo GTV along the twisty roads of Trinity County, in far-northern California, where Armand lives. I let him drive my ’64 Ford, and began to let him work on it. “Let” suggests generosity on my part, but in fact, Remy kept my car running. He was mechanically inclined, could take things apart and repair them, like carburetors, and he could build things from scratch, like tube amplifiers of his own design.

By the time Remy got his driver’s license, on his sixteenth birthday, he’d already spent three months sorting the many electrical and mechanical issues of the 1969 Dodge Dart he had found on Facebook Marketplace. He fired it up and went to eat by himself at the local hamburger stand, then drove up to the mountains to fish. The freedom of the car was not just a matter of autonomy, but self-reliance. In his trunk, he likes to say, are all the tools he would need to completely disassemble and reassemble the car. He drives thirty-five miles round-trip to and from his high school each day, and the car needs endless attention. It’s not uncommon that when we expect him home, he’s lying on the pavement in an O’Reilly parking lot off the freeway, making some emergency repair.

Beyond the required maintenance, Remy is constantly modifying the Dart to make it go faster. This summer, he built a higher-performance engine for it. He has learned much of what he knows from YouTube, and from an online forum focused on “A bodies”—a design once used for smaller Dodge and Plymouth models, such as Darts, Dusters, and Barracudas, which are attractive to hot-rodders for their large motors and light chassis. Reading my son’s posts, I could trace his development from an eager newbie to a forum regular who provided answers with the curt and knowledgeable tone of a middle-aged shade-tree mechanic.

Despite driving a classic myself, my influence here has been minor. I do not have mechanical skills. I did take a shop class, at City College in San Francisco, long ago, but I didn’t learn much. I can change a spark plug, check the oil, and that is it. But I’ve always been near people with mechanical aptitude. I went from being a child on family trips to the junkyard with my father, while he was rebuilding the engine of the 1958 Volvo 544 he’d purchased for thirty-five dollars, to a teenager in tow while Armand scavenged for truck parts, to a mother lined up with her son, who was hoping to find a bigger Dodge engine to rebuild, at a junkyard in south L.A. County, under signs reading no concealed weapons allowed on this property. On that property, I followed Remy down row after row of dead Dodge Dakotas, in a vast place where not even weeds could grow, so toxified was the ground with old motor oils, which made the air pungent with a burnt-onion smell. “That’s from gear oil,” Remy said, “notoriously foul.” He told me that some salvage yards have so much petrochemical waste soaked into the ground that it’s “hydrophobic”: water can’t soak in. It just runs off and puddles.

Salvage yards are grim only to those who don’t see the scores of dead, wrecked vehicles as potential. Remy now goes to them alone, or with his friend Aaron, whom he met through the A-body forum. Aaron is in his forties. Remy’s other best buddy is Armand, who is in his fifties. Both Aaron and Armand have shops with lifts, where Remy spends hours grinding and welding and wrenching. It’s not that he dislikes his peers, but according to Remy, the kids of today don’t really have hobbies. “Why is that?” I ask, and he says, “The internet.” The only people at his school who appreciate his car are the security guards. Middle-aged men approach him at gas stations and tell him to enjoy his ride now, while he can, the implication being that he should have fun with it before he, like them, has a wife to clamp down on his joy. We laugh at these stories, which we agree are “cope,” but also probably true, we suspect, considering how much time cars can take up. The guys at the gas station do not have muscle cars, and instead have wives. The guys at the drag strip with beautiful hot rods and who are traveling solo are “living the dream”—but strike us as a little forlorn. Then again, there are lots of families, including some in which the woman is the crew chief, or she’s the driver, and the kids all have tools in their hands, and everyone seems to love the smell of gasoline.

My father has a fondness for the smell, but mostly, he specifies, for the way gas used to smell, before they changed the composition of aromatics in pump gas in the Sixties and Seventies, years when he was dedicating weekends either to working on his motorcycle, for fun, or on one of our cars, out of necessity. My mother, like me, doesn’t like the smell and long ago banned him from bringing gas-stinking motorcycle parts into the house (and boiling his chain on the kitchen stove).

At the top of Remy’s olfactory hierarchy is the scent of combusted Sunoco 110, a leaded, high-octane race gas that suffuses the staging lanes when the more competitive non-nitro classes are lining up. A lot of people love the smell of race gas, which has a noticeably sweet scent. The sweetness is apparently on account of its benzene content and various additives. Benzene is a known carcinogen, which never once occurs to me as my son and I excitedly walk the lanes at nostalgia events, watching drivers in rumbling hot rods with chromed superchargers punched through the hood move along toward the start. “Ah, race gas,” Remy will say, with excited contentment, a state of joyous well-being that every parent wants for their child, and which becomes that parent’s own well-being. Perhaps this is why I, too, have come to like the smell.

Meanwhile, E85, an ethanol-gasoline blend, smells to Remy of “old wine and dead socks” (“but not necessarily in a bad way,” he clarifies), and he will immediately detect the presence of even a single car running it. E85 can be bought at some gas stations; it’s typically used by the true “sportsmen”—those without sponsorships and expensive trailers, who drive their turbocharged street cars to the drag strip in the tradition of “run what ya brung.”

Nitro has marquee billing as the most violent fuel of the fastest cars, with a unique smell that anyone can recognize once they’ve been introduced. To my nose, it is vaguely sour and slightly fermented but aggressively chemical, like flat beer and industrial fertilizer (but not necessarily in a bad way). Many drag-racing enthusiasts claim to love the smell of it, even if it can sting the eyes like teargas if you’re standing too close. A faceful of its fumes will knock a person unconscious, which is why drivers wear gas masks. “Uncle Tony,” a muscle-car and street-racing enthusiast and YouTuber whom Remy used to follow devotedly, talks about nitro as a kind of “addiction.” According to Tony, in one of his livestreams, he’d be jonesing to get to the track and fire up the car to get his hit. Tony was so fond of nitro that he would put it in his lawn mower, as he tells it. When the neighbors saw him getting ready to cut the grass, they would hurriedly call their kids inside.

If he were a teenager in the Seventies, Remy muses, he’d have friends his age who also loved working on cars, and there’d be a lift at his high school auto shop. But there is no auto shop, and the kids don’t have hobbies, on account of the internet. And yet the internet has taught Remy how to work on cars. It has connected him to a world of like-minded people.

Besides Uncle Tony, his early YouTube role models were David Freiburger and Mike Finnegan, the longtime co-hosts of a show called Roadkill, whose motto and ethos is “Don’t get it right, just get it running.” In each episode, Finnegan and Freiburger throw themselves into joyously impractical self-dares, like installing a 426-cubic-inch Hemi, the ultimate hot-rodding motor, in a 1975 AMC Gremlin, the ultimate lemon, which they christen the “Hemi Gremmie.” Nothing is scripted, and the plot often ends up structured around failure, which, to their initial surprise, turned out to be an incredibly popular narrative hinge.

Roadkill is shot usually on location, but this past May, they were filming at a shop in Gardena, California, that is leased by the MotorTrend Studio and mostly used by another popular show, HOT ROD Garage. When Remy and I showed up, Freiburger and Finnegan were working on a Roadkill favorite: a 1950 Ford dump truck called Stubby Bob, whose engine they had installed behind the cab so that it could do wheelies. Their plan was to drive it all the way to Yuma, Arizona, where they would outfit it with paddle tires and attempt to race it at a sand drag strip.

I hadn’t been aware there was even such a thing as drag racing on sand. “There’s everything,” Finnegan said. There are people who drag-race rototillers, he told us. Also belt sanders. And remote-control drag cars. “There are people with purpose-built trailers, but for their RC cars.” Rototiller racing’s world championships are held in Arkansas. Later, I found evidence online of “rice tractor” racing in rural Thailand. The Thai racers seemed more ferociously competitive than their brethren down in Arkansas. But to be fair, in rototiller racing, the driver runs behind the tiller, so his speed is limited to that of a human, while the Thai racers crouch over the rear axle of a four-wheeled machine as it shoots through the dust like a turbocharged chariot.

Finnegan is the more outgoing and affable, while Freiburger, known for his encyclopedic knowledge of hot-rodding history, describes himself as a recluse. For more than a decade, he was the editor of HOT ROD Magazine, where Finnegan was an associate editor. In the early Aughts, as magazines were beginning to fail, they would hold despairing meetings about how to get people to engage. “We would sit around and wonder, How do we get kids to want to read?” Finnegan told us. “How do we get kids to even want to have a driver’s license? We were thinking we’d go to high schools and pass out magazines or try to help get auto shops going again. And then YouTube happened.”

In the first Roadkill episode they filmed, the two attempt to drive a 1968 Ford Ranchero from Los Angeles to Alaska, to race it on ice. They experience a series of mechanical failures, for which they make repeated visits to auto-parts stores, and confer on the side of a highway in frigid weather. They don’t make it to Alaska, but they do encounter snow when they deviate to Utah and Arizona, where they do gleeful doughnuts.

Finnegan had figured that no one would want to watch a show about two guys who set out for Alaska and don’t get there. But he came to understand that people just wanted to see what it’s really like to hit the road with minimal tools and minimal funds. Roadkill was immediately popular, particularly among young people. “It was four-year-old kids. A ten-year-old. A fifteen-year-old, and they would get their parents into it,” said Finnegan. One of the episodes has garnered fifty-five million views. “Suddenly we had parents going out and buying ’69 Chevelles, and they would tell us, ‘We never thought we were into cars. We never thought we could do any of this, but I watched you guys on YouTube, and it seemed attainable. And so now me and my kid are in the garage. I bought my first welder. I’m working on cars.’ ”

Roadkill has now migrated to cable television and streaming services, where it continues to attract millions of viewers. A lot of people who watch the show, Finnegan told me, do not live near a drag strip and might never visit one. But there’s a lot of overlap between these popular hot-rodding shows and the world of nostalgia racing. Alex Taylor, the co-host of HOT ROD Garage, drag-races a 1955 Chevy in her spare time. Her car is wickedly fast (six seconds in the quarter mile), but it’s street legal, and she regularly drives it hundreds of miles, from drag strip to drag strip.

When I mentioned to Finnegan that we were going to Beech Bend Raceway, he said that he and Freiburger had been there just after the nearby Barren River rose up, flooded the track, and ruined an ambulance. They persuaded the track owner to sell the vehicle to them, never mind that it was waterlogged and mud-caked. They were headed to HOT ROD Drag Week, some 350 miles away, near Columbus, Ohio, and were looking for wheels to get them there, Finnegan explained to me. They got the ambulance running but didn’t realize it was full of black mold until they both started coughing on the highway heading north. They pulled over and got cleaning supplies and scrubbed it out. Next, the alternator failed, a special model that cost $800 and would be impossible to find. So they bought a generator, strapped it to the back door of the ambulance, taped an extension cord over the roof to a battery charger that they zip-tied to the grille, and kept going. They rolled up to Drag Week with the sirens wailing, announcing their arrival over the vehicle’s loudspeaker. “Way more fun than driving a rental car,” Finnegan told us. I asked him whether the episode was available online. “Oh, it wasn’t an episode,” he said. “This was just us out having a good time.”

It was almost noon, and Remy and I had staked out a slim wedge of shade next to the Beech Bend timing tower while we waited for elimination rounds to commence. This was the third and final day of the Nostalgia Nationals, and large crowds had amassed behind the staging area, to be closer to the action. A very old man in a motorized wheelchair, bypassing signs warning spectators to stay outside the start area, rolled toward me like my spot in the shade belonged to him. I ceded it. There were a lot of these old-timers at nostalgia-drag events—mobility impaired, sun-weathered to the point of absolute ravage, sometimes towing an oxygen tank. One cannot ignore the bodily decline of many enthusiasts, and yet I’m not convinced it signals the end. Instead, the nostalgia scene feels curiously future-facing, even if it’s counterintuitive to declare that the past feels like the future. The retro-style diner, for instance, and its rehash of the Fifties, has always depressed me, striking me as nothing but stale longing for an innocence that never was. People at nostalgia-racing events do play the same oldies that are lifelessly blasted at a Johnny Rockets (Famoso hosts an annual event called the Good Vibrations Motorsports March Meet, named for an auto-parts company sponsor). You might pass a swap-meet booth featuring a mannequin outfitted like a carhop, in roller skates and a dusty wig. Yes, the old guys are partly there to relive their pasts. But the core energy, among those who build and race dangerous and archaic machines, is a fierce vitality. There are big-time NHRA drivers who are converts, having found the nostalgia world more appealing and homespun, more eccentric, ecumenical, and showy, and in many ways more terrifying and raw.

In the staging lanes, dragsters were lined up, towed by ropes behind other cars and trucks, each driver suited up and sweating profusely behind the wheel. Jay Rowe, a chaplain from a ministry called Racers for Christ (RFC), moved from dragster to dragster praying with drivers before their run. We had met Chaplain Jay that morning. A cheerful man in his early seventies, with ramrod posture and a plush gray mustache, he visits injured drivers in the hospital, and performs funeral services for racers and their families.

I asked him if he ever found prayer difficult. He said that when you don’t know what to say to God, you remember that he created you, and that an elevated form of communication passes through to address him. You just let the prayer flow, he said; you might not even hear it. I’m sure he could have explained a bit more about how this works had he not needed to abruptly excuse himself to go prepare for his own race.

Chaplain Jay was running in the “gasser” class— classic cars with a famously chunky idle and a raised front end, giving them a mean and exciting look. His own was an egg-yolk-yellow Thirties coupe with showtime painted in huge letters flanking both sides. He won his round, and practically emitted a phosphorescence as he spoke of it afterward. It was jarring to hear Chaplain Jay recount his victory, as if a second man had emerged. Not a chaplain, but a winner. A guy he races with had lined him up exactly right, in order to avoid treacherous bald spots in his lane. “I was straight as an arrow!” His competitor had “broken out,” which means he went too fast. Racers in the “sportsman” classes are matched in brackets against competitors with the same dial-in time—the estimated interval it will take the car to reach the finish line. The objective is to run as close as possible to the dial-in time. (Undermining the myth that drag racing is simply about going fast, bracket races warrant a technically calibrated plan: go too fast and you lose.) In this case, the dial-in time was 9.0 seconds. Chaplain Jay ran a 9.002. His top speed was 146 miles per hour. “Best pass I’ve had all weekend,” he said, beaming. He’d smoked his competitor. Not with God’s help, but with strategy, skill, and luck.

Our first encounter with an RFC chaplain had been back at Famoso. He was maybe forty, with a long goatee, and wore pristine white mechanic’s coveralls. “The guys who request me,” he told us, “I pray with them. The guys who don’t, I pray for them.” This seemed fair. I mentioned the chaplains to an old associate of mine, “Slim Jim” Hoogerhyde, who races land-speed vehicles and has set many records at the Bonneville Salt Flats, where RFC has a presence. “My wife and I have a rule,” he said. (His wife is also a land-speed record holder.) “In our pits, no politics, no religion.”

Slim Jim is someone I know from the San Francisco motorcycle scene of the Nineties, and is to the left, politically, of some in his racing communities. In 2007, he began land-speed-racing electric vehicles. “We all want clean air, clean water, but at the end of the day, I want to go fast, whether it’s gas or electric,” he told me. “I have eight hundred Trump motherfuckers all the time pointing out my contradictions—‘You drove a gas truck here, you’re not saving the planet’—and I’m like, No, I’m trying to go three hundred miles per hour! It doesn’t bother me. It fires me up.” He told me that racing EVs feels like early hot-rodding. “I’m sure it drives the old guys nuts to have me compare it to the Forties and Fifties, but it feels identical to me. We’re going to the junkyard to get parts, and pushing them way beyond their limits.”

At the drag strip, you might see a beach towel with Trump’s likeness for sale, but people do not tend to bring up politics. The environment has no need of such abstractions. You see the chaplains with that fish logo on their shirts, but the drag strip is not Christian. I would describe it instead as congregational. There can be three generations of a single family working on a pit crew. Or large assemblies of friends who share their tools and parts with their neighbors. Someone might loan a carburetor to a stranger who is running against them.

At Eagle Field Drags, outside Fresno, we had met a driver named Greg Adams. “The thing about drag racing,” he told us, “is it turns me toward people.” Greg’s team wore matching bright-orange T-shirts onto which they’d freshly stenciled pops in black spray paint, a tribute to Greg’s late father, who had also been a drag racer. They’d held his memorial service at Eagle Field the year prior: “We scattered his ashes in the prep we put down at the start, for tire traction.”

Every driver “smokes the tires” at the start, to warm them up, make them sticky, and clean them of any grit they’ve picked up. Greg rolled over his father’s ashes and did his burnout, embedding his father in the track before he made his run. The strip at Eagle Field never gets scraped. The burned rubber just builds up, like a cast-iron skillet acquiring carbonized layers of seasoning. “Those ashes will be there probably forever,” Greg said.

Unlike Beech Bend, Eagle Field is not an NHRA-sanctioned raceway but a World War II–era airstrip. The environment is sportsmen-class friendly and lax. We saw a jet-engine dragster nicknamed The Beast that was spitting thirty-foot flames, and a car whose carburetor caught on fire at the start of a race and burned away until someone unhurriedly waved a ball cap at it. People camp at Eagle Field. Their kids look 4-H savvy, but also wild and free. I saw a girl of about eight speed past on a small motorcycle, riding barefoot, with an even younger barefoot girl on the back. I saw boys with long hair, in cutoffs and cowboy boots, a mix of signals that defied stereotypes. But also mullets, sunburns, and billowing don’t tread on me flags. Unlike at other California raceways, the crowd seemed mostly white, with some Latinos. When I suggested to Wallace Stevenson, who had come alone to spectate and seemed to be the only black person there, that the demographics appeared less diverse than at some other nostalgia events, he laughed. “Oh, there is some real hillbilly action here,” he said. “But they’ve all seen me so many times. I’ve been coming all these years, and it ain’t no thing.”

Wallace is originally from Stockton, where he got into hot rods as a teenager in the late Sixties. Stockton’s racially segregated neighborhoods meant that there were absolute no-go zones for black people, he told us, but being into cars “bridged the communication.” People who were into hot rods were on equal terms. “There are relationships I made at that time, as a kid into street racing, that carry forth to this day. If you have a love for cars, you can always talk about that.”

Brian Lohnes, lead broadcaster for the NHRA, told me that when he announces at grudge races (outlaw-style street racing, but on a track) in Mississippi and other Southern states, he’s typically the only white guy in the place. But, he said, “As soon as you roll through the gate, it does not matter. Everybody’s there for the same reason. It’s a very unique thing.” Lohnes told me that it’s the inclusivity that fascinates him most about drag racing. He attributes the sense of a single shared world to racing’s origins as an activity perceived as a national menace. “Everyone involved looked different, everybody that did this stuff was against the cops and the government. It didn’t matter if you were black or Mexican or white. And the sport never shied away from that or lost it.”

The inclusive spirit isn’t part of any program to diversify as an ethical obligation or goal. It’s a natural feature of the sport: the love of modifying cars to go fast isn’t claimed by any single racial identity. At Irwindale, Famoso, and Beech Bend, we saw Latino drivers and families, Filipino drivers and families, and lots of black drivers, black team owners, black crew chiefs. The car that came away Pro Stock champion at Beech Bend, a 1973 Plymouth Duster, was driven by Ted Peters, who is black. His crew chief, also black, told us that he and Peters had been friends since they were four. In a different section of the raceway’s pits was an informal consortium of black drivers who had brought a chef down from Indianapolis to cook for them.

Drag racing was diverse from the very beginning, when soldiers came home from World War II and began to tinker and test out vehicles on decommissioned airstrips. One of the most famous drag cars of all time was a blue Willys gasser that dominated in the early Sixties. Its team was called Stone, Woods, and Cook—three guys, two of them black and one white, traveling together through pre-civil-rights America.

Japanese Americans, meanwhile, had been visionaries of land-speed racing since even before the war, and, upon their release from the internment camps, were welcomed back into the hot-rodding community. A legendary car club in San Diego, the Bean Bandits, was founded by a group of Mexican Americans but included racers who were black, Filipino, Japanese, and white. The Bean Bandits were a formidable presence on drag strips and dry lake beds throughout the Fifties. Over the decades, the stories non-white drivers told about bigotry and intolerance took place mostly beyond the drag strip. When Eddie Flournoy, one of the earliest black nitro tuners, was traveling as a Top Fuel mechanic in the Fifties, he had to sleep in his car, because hotels were for whites only. “They had their rules,” he once said. “But when I got to the racetrack, I had my own rules—winning.”

Because of the infernal heat and swamplike humidity at Beech Bend, there was a lot of prep work to be done before the Nostalgia Nationals elimination rounds could commence. Workers were cleaning away oil and tire debris with mops and brooms. Beyond them, the end of the quarter-mile track pooled into a mirage of liquid black. Its surface, I later learned, reached 138 degrees Fahrenheit, making traction almost impossible.

Remy and I were chatting with one of the security guards, a guy named TJ, who started telling us about a ’62 Chevy Bel Air he used to own. We got into such an animated conversation that we didn’t notice the national anthem begin. The men in front of us turned around and gestured for us to remove our hats. As a woman began to sing over the loudspeaker, TJ whispered that his Bel Air still had its original straight-six engine. “That was a really fun car.” He started to tell me about a ’62 Comet he’d recently picked up, at which point someone shushed us. We stopped talking and listened to the singer hit her octave leaps.

As the daughter of nonconformists, I refused to pledge allegiance as a child. But Remy doesn’t stand for that kind of performative immaturity. We took off our hats and held them to our chests like everybody else. I’ve done this at other sporting events, but it feels less like an empty ritual at a drag race. There’s naked emotion in the air, a sense that identifying as an American has great meaning for many of the people present. But the peak of patriotism I’ve seen at drag events was at Eagle Field, when The Beast, which sports a 1960 Navy fighter engine, was fired up and getting ready to make its run. A very old man bellowed “Freedom!” over and over as he held up his phone to film the flames and smoke spilling wildly from the rear of the jet. “Frrreeedommm!”

“Wow,” I’d said to Remy. “Look,” he replied. “You can’t do this kind of stuff in, say, Germany.” In many countries, the modification of street-legal cars with performance parts is strictly regulated. If U.S. laws are more permissible with regard to hot-rodding, though, California is among the freest states, because it requires no safety inspection for any passenger vehicles and no smog inspection for pre-1975 cars. If you install a stroked Hemi with a blower in a 1970 Road Runner, the California Department of Motor Vehicles is never going to know about it. And if a cop pulls you over, it’s probably just to admire your setup. (Even though hot-rodding roots are deeply antiestablishment and anti-cop, cops are famous for not issuing tickets to those running modified classics.)

TJ went back to work, and Remy and I moved up to an area just behind the burnout box, a trough of water that drivers roll through before smoking their tires. Most everyone wearing media vests was alongside the track, in order to film, while we positioned ourselves not to capture visuals, but to feel.

I knew what to expect, and yet the first Top Fuel dragster to warm up its tires was a violent jolt to the senses, even with ear protection. The burnout requires sudden, high-rpm revving, and it always takes me by surprise. Each machine was surrounded by a crew in matching uniforms—this was the Top Fuel finals, and the teams that get this far tend to be well organized and at least semi-sponsored, such as the Champion Speed Shop car, an arresting slingshot-style dragster, black with gold lettering and a closed driver compartment cantilevered behind its rear wheels.

Techs wearing gloves rubbed their hands over its rear tires to remove grit with fastidious care, like coaches attending to a fighter’s shoulders before the final round. When the cars were staged, the start lights (the “Christmas tree”) went from red to yellow and finally to green. They were off.

Full acceleration for the quarter mile far outstrips the roars of the burnouts. The sound fractured the air, made the hairs on my arms shiver. I felt it deep in my chest, a kind of internal impact, like something was pummeling my heart. This can’t be healthy, and yet it’s a thrill once you develop a taste for it. Half the cars lost traction, on account of the heat. Next were the funny cars. Class after class, we watched vehicles rip down the track.

I can’t say it was expected that I would come to enjoy being brutalized by sound and heat and smoke. The way cars do their burnout, back up, stage, then careen forward when the lights go green is a ritualized order that now seems classical to me. A Platonic form has taken residence in my mind: a woman standing before a staging dragster, her legs slightly apart, arms raised to position it for takeoff, her thighs a formal echo of the car’s dramatic rear “slicks”—the tires.

In the early and mid-Seventies, the most iconic such woman was Jungle Pam, who would line up Jungle Jim’s funny car in short shorts, her large breasts spilling from a halter top, looking more hippie chick than Hooters. At the time, Shirley Muldowney and a tiny handful of other drivers were the only women in a men’s sport. Now women compete against men both in the mainstream NHRA and in nostalgia racing. Even as you might see some reprising their own version of Jungle Pam’s routine, theatrically lining up cars for the start while dressed in tight clothes and go-go boots, you see women drivers behind the wheel in every class of vehicle. Legendary tuner and team owner Alison Lee was standing at the start when her grandson, Tyler Hilton, won the Nostalgia Nationals championship in 2023. One of the larger nitro funny-car teams at Beech Bend, which was prepping Eddie Knox’s Problem Child, included a young woman removing valves from a cylinder head. She lapped them, methodically and carefully, one by one, then took a break and walked over to a baby in a bouncy chair near the pit crew. I’d noticed the baby earlier, but hadn’t realized it belonged to the mechanic until she picked it up, changed its diaper, and continued on with her work.

Sixteen-year-old Ayden Kennedy was also crewing for Problem Child, and it was clear he was no intern but a seasoned tuner. Dressed in black, he was assigned to the clutch and to the engine’s bottom end: the most difficult job on a crew.

Ayden was from Bethlehem, Georgia, a town of 750 people where he lived with his family on a rural cul-de-sac. He was calm, handsome, modest, and slight. He started working on cars with his grandfather when he was three. He was driving by age six or seven. He and his grandfather hot-rodded trucks, lawn mowers; they’d be outside, tinkering, until three in the morning. His mother, Laura Kennedy, sent me a video of Ayden at age five, rebuilding the rear of a Dodge pickup truck and explaining every step. Before he could even reach the pedals, he learned to drive trucks, joining his dad, a trucker, on runs to Florida and Alabama. He can operate excavators and even a logging skid steer.

Ayden had gotten involved with Top Fuel three years earlier, when he came up to Beech Bend for the first time. He’d begun chatting with a team mechanic, who was impressed with what he knew and invited him to help out with finals the next day. Ayden showed up and worked on the dragster’s clutch. After that, the team decided to fly him out to Boise, Idaho, to work with them for a week at another track. He was thirteen years old.

Like Remy, most of Ayden’s friends were adults, though he still had two more years of high school, where he was enrolled in a dual program to get a diploma and a vocational certificate in welding from the local community college. Outside school, he worked a job at a shop that repairs and sells used lawn mowers. He was already talking about forming a Top Fuel team when he turns eighteen, with some of the guys he’d met on the nostalgia circuit. He wasn’t sure about a career but understood that his mechanical skills would give him plenty of options. “I grew up poor,” Ayden said, smiling, “so I had to learn how to work on stuff.”

If Ayden ascribed his own ability to learn, his intrinsic talents, to poverty and personal circumstance, simply being poor doesn’t account for his mechanical abilities. Similarly, Remy’s middle-class upbringing doesn’t account for his own aptitude, which isn’t dissimilar from Ayden’s, even if Ayden is further along with his welding skills.

When he was five or six, Remy described me and my husband as people who “push paper.” “I’m not gonna push paper like you and Daddy,” he said. “You guys just sit there. I am going to use my body in my work.” I don’t know what Remy will end up doing. When he’s not in school, he works on cars, studies chemistry, and plays piano. Though tinkering and chemistry have some tangential overlap, the people in his chamber orchestra have no idea he built a motor this summer, and most of his car friends are probably unaware he’s a classical pianist. If his passions remain separate, a kinship with skilled tradespeople, with people who physically make and do, runs deep.

In the nostalgia scene, many work day jobs as welders or electricians, service technicians or carpenters. Brant Inglis is a gunsmith. These are all jobs that require what my father’s German motorcycle mechanic, Ziggy Dee, once referred to as Feingefühl: a fine touch. Feingefühl is receptivity and responsiveness, a kind of tact, even, a wisdom concerning one’s relation to objects: how much force to apply or not to apply, an ability to navigate nuance by feel.

Those who work with their hands are constantly testing their Feingefühl. When a mechanic installs cam bearings in the motor they are rebuilding, intent on inserting them straight, they summon Feingefühl. When a pianist plays Prokofiev, they also summon Feingefühl. In many activities, not just music, there is an aural dimension to touch and tact. Talented mechanics are good listeners. They know the sound of a bad wheel bearing, or of an exhaust leak. These skills are not obsolete: there is a national shortage of automotive technicians, and companies like Ford are investing heavily in the NHRA, Brian Lohnes told me, to try to recruit young people. At Famoso, I’d met interns on Top Fuel teams from the local community college. Those students will find gainful employment as mechanics if they want it.

Others of us—myself included—do not think with our hands, and cannot respond to many of the signs emitted by the material world. Instead, our relation is passive. The world has come to invite this passivity. So much of it cannot be held or touched. It requires no refinement of our senses. A touchscreen, for instance, involves no actual touch. On iPhones, we use our fingers to press invisible buttons that send signals. Triggering these buttons requires no nuance or modulation. The glass surface gives only simulated feedback. Their supposed function—to integrate shopping, news, entertainment, and communication—no one seems to have asked for, or wanted. It’s not a phone so much as an addictive diversion. We know it’s a diversion, but what it’s a diversion from is harder to admit, because the answer is everything.

Many of the consumer goods that are accessed on screens are things we buy but do not own—a streaming service, a “licensed” software program, a rideshare. And of the things we do own, most are designed to be discarded when they break. Modern technology is not meant to be disassembled, studied, fixed. We have been de-skilled, almost invisibly, as if it happened without our consent.

At a series of “cloud kitchens” in a faceless, two-story commercial building near my house, young men hover around the entrance, scrolling on their phones. They are almost always wearing sweatpants, driving late-model cars, probably leased. They work for Grubhub or Uber Eats, and are waiting to deliver orders to someone who is also scrolling on a phone, driving a leased car, wearing sweatpants, someone who might be a little, or even significantly, above them in social class, an office worker, a corporate lawyer, who streams a lot of stuff and has access to a “wealth” of information, but they share alienation in essential ways. The men bringing the food and the ones eating it all seem to me like stray cats, surviving on the scraps of our modern dispossession. I’m not free of this system, an innocent, but it’s easier to see it and name it in strangers, as they scroll and wait for industrial food.

I recall a late-Sixties Nova rumbling past me and Remy through the staging lanes at Irwindale with an Uber logo in its window. It was a symbol visited upon us from “real” life, whose thinnest, cheapest, and most disposable conditions were usually suspended at the drag strip, where people live in a moment-by-moment relay with the material world, seizing upon what can be not only truly owned, but even better, possessed: machines that are taken apart, studied, learned, repaired, and most importantly, modified for a new use. This is the essence of hot-rodding. It is the opposite of passive consumption, of leasing, licensing, renting, subscribing.

A commodity, by definition, is a thing that is used, that does not yield its internal logic. To use a commodity is not to possess it. Possession requires mastery. If hot-rodders are not typically of the elite propertied classes, they have broken with a form of passive consumption that most in our society take for granted. They have a wealth that others lack. They have knowledge and mastery, and the joy and rightness from which they derive. These things—joy, mastery—cannot be bought. Trying to purchase them will only put you further in the hole.

Remy and I got caught up talking to so many people, visiting so many pits, watching final elimination rounds (Tyler Hilton was the Nostalgia Nationals champion yet again) that we were surprised to find that it was almost six o’clock, and we had to rush to Paul Brown’s trailer, where I was due to suit up for the cackle show.

The sun was low, suffusing the smoky air in a baked orange-yellow glow, as Remy and I walked alongside the Doug Thorley Corvair. Paul was behind the wheel, steering it as his friend Reilly towed it with the golf cart. We were among a gleaming procession of other funny cars and Top Fuel dragsters. I heard the twangy opening of “Far Away Eyes”—I was drivin’ home, early Sunday mornin’, through Bakersfield—as a Chevy Nova once owned by Paul’s friend Randy Walls pulled up alongside us. Randy had died two days earlier, after a long battle with cancer, and now the car was here to memorialize him. As Mick Jagger continued his send-up of country gospel and we all moved along like a small-town parade, Paul yelled to the guys towing the Walls car: “Hey, you want to race?”

“Is that thing a hybrid?” one of them hollered back.

The stands, which line both sides of the raceway, were full as our procession turned onto the track itself. The soles of my shoes clung to the sticky surface as we walked down the track toward our designated spot, among two long rows of cars. The Corvair needed some distance from the other vehicles, Paul told the event coordinator, because its exhaust ports angle straight out, rather than sweeping up and back, and he didn’t want to accidentally torch anyone nearby. I zipped up the jacket, put on the silver fire boots and the rest. I felt like an astronaut, but sweatier.

Getting behind the wheel of a funny car is a procedure if you’re not used to it. I’d practiced before we’d begun to wheel the car over from Paul’s pit area, and angled myself in. I was gloved, masked, helmeted, and slightly terrified. I knew Remy was filming from some safe distance, but could not see him. The huge engine and its tall blower rose up in front of me, half-obscuring my view of Paul and the men who were helping him fire up the car. I thought of what Don Garlits said about his first pass in the rear-engine dragster he’d built: finally, he could see.

Over the PA system, Brian Lohnes initiated the countdown. Paul and his crew, the fans in the stands, my own son, who had encouraged this, were as far from me as people could be. In my fireproof cocoon, I realized that the respirator smelled faintly of cigarette smoke. Paul Brown. My new friend. That I would normally dislike this smell did not inhere. It kept me company, perhaps not unlike how those autographs keep Brant Inglis company, there in the lining of his fire mask, up against his face.

The funny car was started. It was loud, but this was only the methanol. When they switched it to nitro, it began to pop and shake. Fire shot from the headers. Paul leaned over the motor and cracked the throttle. The noise was an extreme sensation, multidimensional. My very cells revved. How could someone drive this? I thought. How could they willfully step on the accelerator and make this happen?

When it was over, I got out and removed, with Remy’s help, the goggles, helmet, and fire mask. Sweaty, dazed, and triumphant if in a minor way—all I’d done was sit behind the wheel, and thereby grasp the distance between me and the people who drive these monsters—I posed for pictures. The track was now open. Fans could come down from the stands and wander. As I spoke to various spectators, I watched two little girls goofing around, barefoot, testing the track’s stickiness, laughing, tripping, falling, rubbing their heels into the gluey surface, which deposited blackish grime on their feet and legs. Remy noticed them also. We both thought of the little girls at Eagle Field zooming past us barefoot on a motorcycle. Not with judgment. It was just an image. Barefoot girls. Light and not reductive, an image that spoke to us of the rest:

Feet plus world.

Track plus heat.

Hand plus tool.

Fuel plus detonation.

Speed.

Possession.

“He knows things about the world,” Laura Kennedy had told me of her son Ayden, “that a lot of grown men don’t.”