Bitbanging 1D Reversible Automata

One Dimensional Reversible Automata

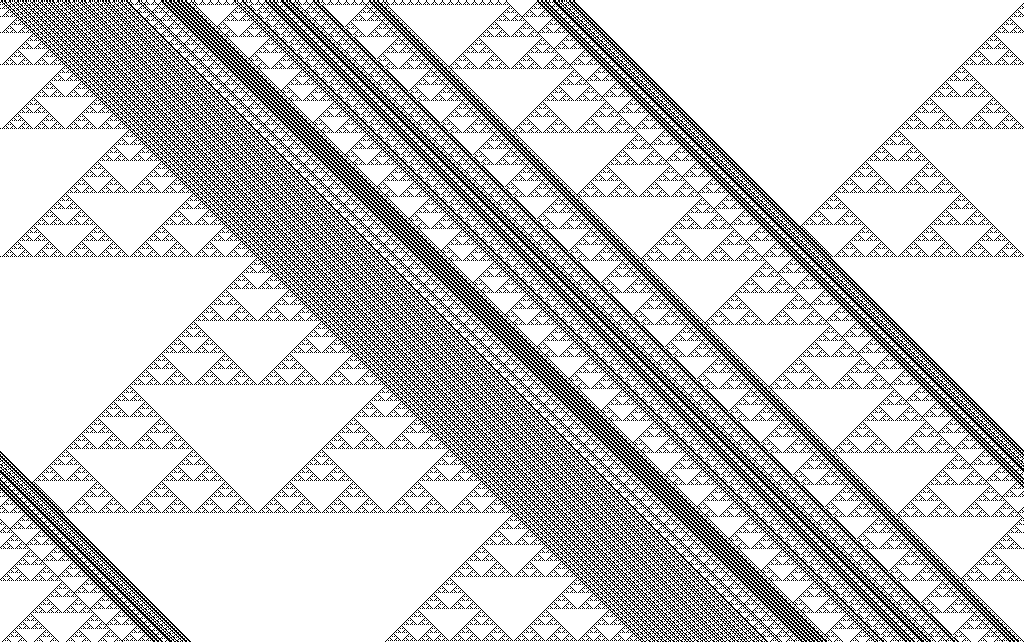

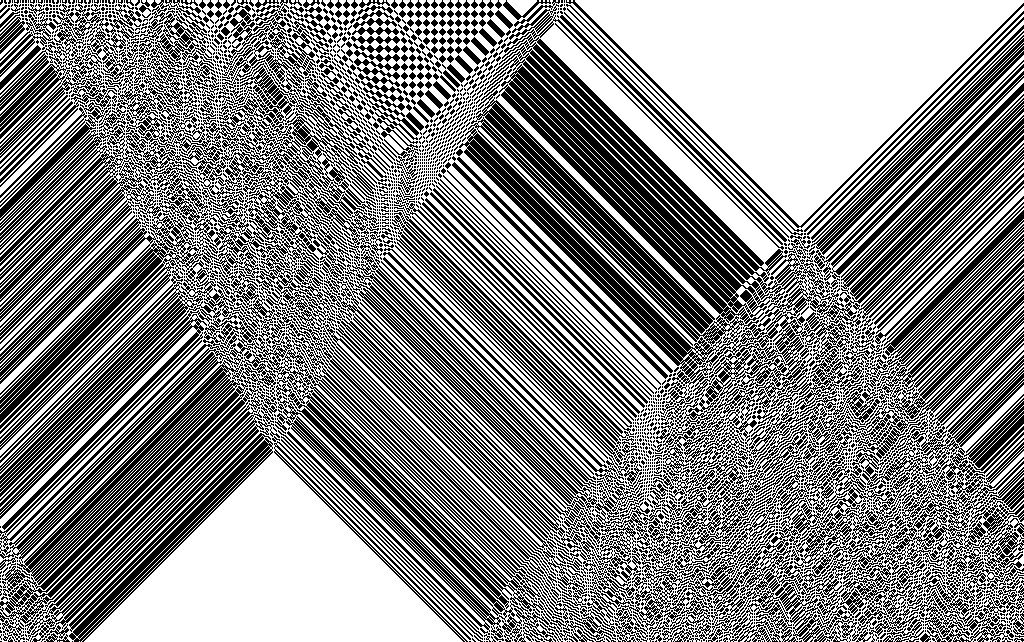

I created a demo for the GFXPrim library. It

implements and displays a nearest-neighbor, one-dimensional, binary

cell automata. Additionally it implements a reversible automata,

which is almost identical except for a small change to make it

reversible. The automata is displayed over time in two dimensions,

time travels from top to bottom. Although in the reversible case

time could be played backwards.

The automata works as follows:

- Each cell has a state, which is on or off, black or white,

boolean etc. - At each time step, the state of a cell in the next step is

chosen by a rule. - The rule looks at a cell’s current value and the values of its

left and right neighbors. - There are 23 = 8

possible state combinations (patterns) for 3 binary cells. - A rule states which patterns result in a black cell in the next

time step. - There are 28 = 256

possible rules. That is, 256 unique combinations of patterns.

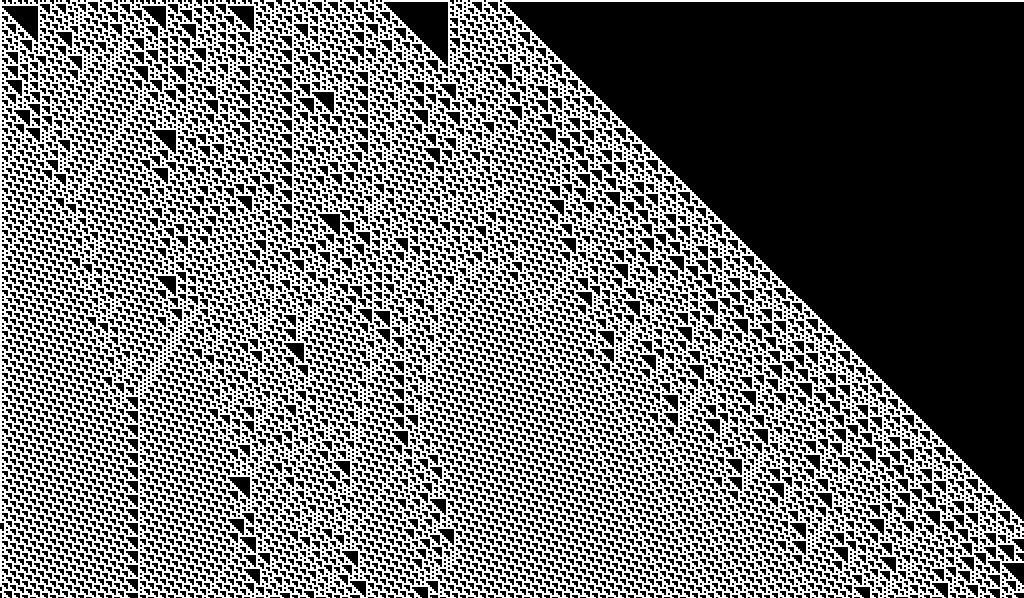

So a pattern is a 3 digit binary number, where each digit

corresponds to a cell. The middle digit is the center cell, the high

order bit the left cell, the low order bit the right cell. A rule

can be display by showing a row of patterns and a row of next

states.

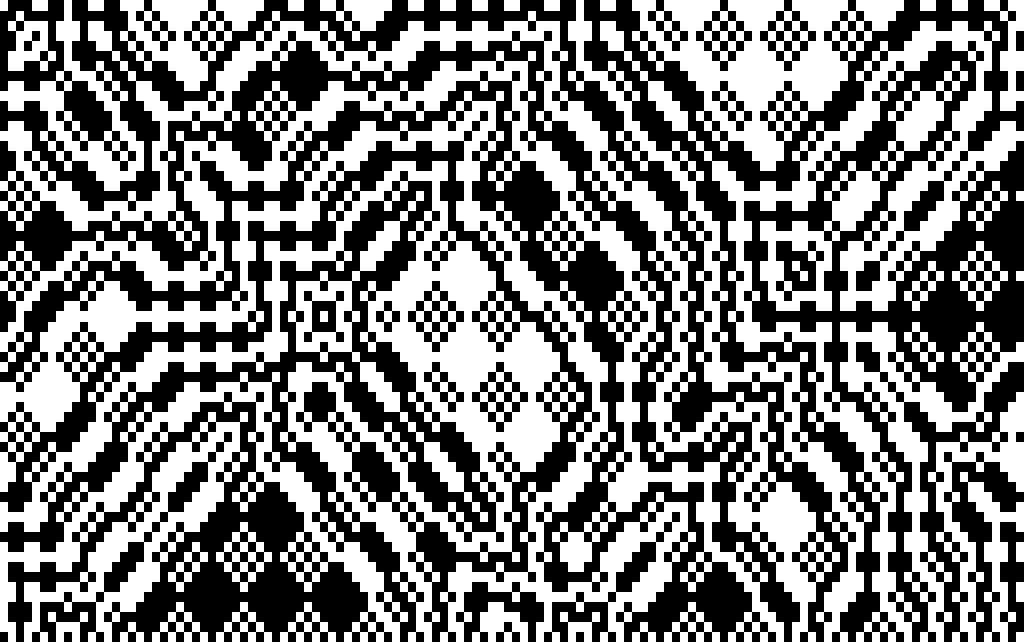

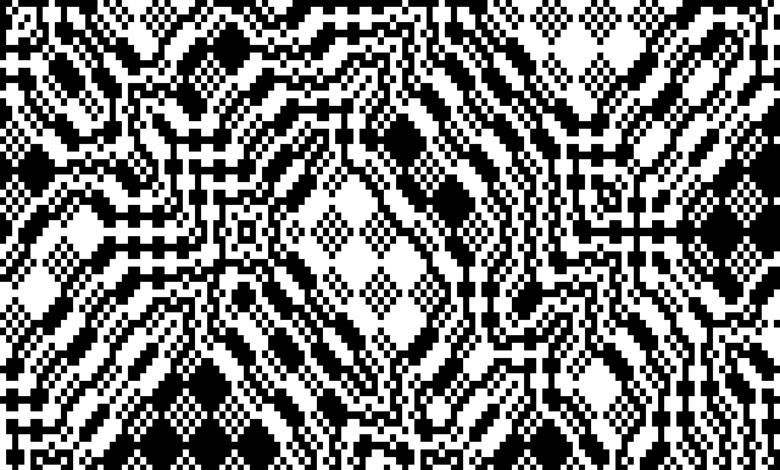

Above is rule 110, 0x6e or

01101110. It essentially says to match patterns

110, 101, 011,

010, 001. Where a pattern match results in

the cell being set to 1 at the next time step. If no pattern is

matched or equivalently, an inactive pattern is matched, then the

cell will be set to 0.

Again note that each pattern resembles a 3bit binary number. Also

the values of the active patterns resemble an 8bit binary number. We

can use this to perform efficient matching of the patterns using

binary operations.

Let’s assume our CPU natively operates on 64bit integers (called

words). We can pack a 64 cell automata into a single 64bit

integer. Each bit corresponds to a cell. If a bit is 1

then it is a black cell and 0 for white. In this case

we are using integers as bit fields. We don’t care about the integer

number the bits can represent.

The CPU can perform bitwise operations on all 64bits in parallel

and without branching. This means we can perform a single operation

64 times in parallel.

If we rotate (wrapped >>) all bits to the right by one,

then we get a new integer where the left neighbor of a bit is now in

its position. Likewise if we shift all bits to the left, then we get

an integer representing the right neighbors. This gives us 3

integers where the left, center and right bits are in the same

position. For example, using only 8bits:

| left: | 0100 1011 | >> |

| center: | 1001 0110 | |

| right: | 0010 1101 | << |

Each pattern can be represented as a 3bit number, plus a 4th bit

to say whether it is active in a given rule. As we want to operate

on all 64bits at once in the left, right and center bit fields. We

can generate 64bit long masks from the value of each bit in

a given pattern.

So if we have a pattern where the left cell should be one, then

we can create a 64bit mask of all ones. If it should be

zero, then all zeroes. Likewise for the center and right cells. The

masks can be xor’ed (^)

with the corresponding cell fields to show if no match occurred.

That is, if the pattern is one and the cell is zero or the cell is

one and the pattern is zero. We can invert this (~) to

give one when a match occurs.

To see whether all components (left, right, center) of a pattern

matches we can bitwise and (&) them

together. We can then bitwise or

(|) the result of the pattern matches together to

produce the final values.

If we wish to operate on an automata larger than 64 cells, then

we can combine multiple integers into an array. After performing the

left and right shifts, we get the high or low bit from the next or

previous integers in the array. Then set the low and high bits of

the right and left bit fields. In other words we chain them together

using the end bits of the left and right bit fields.

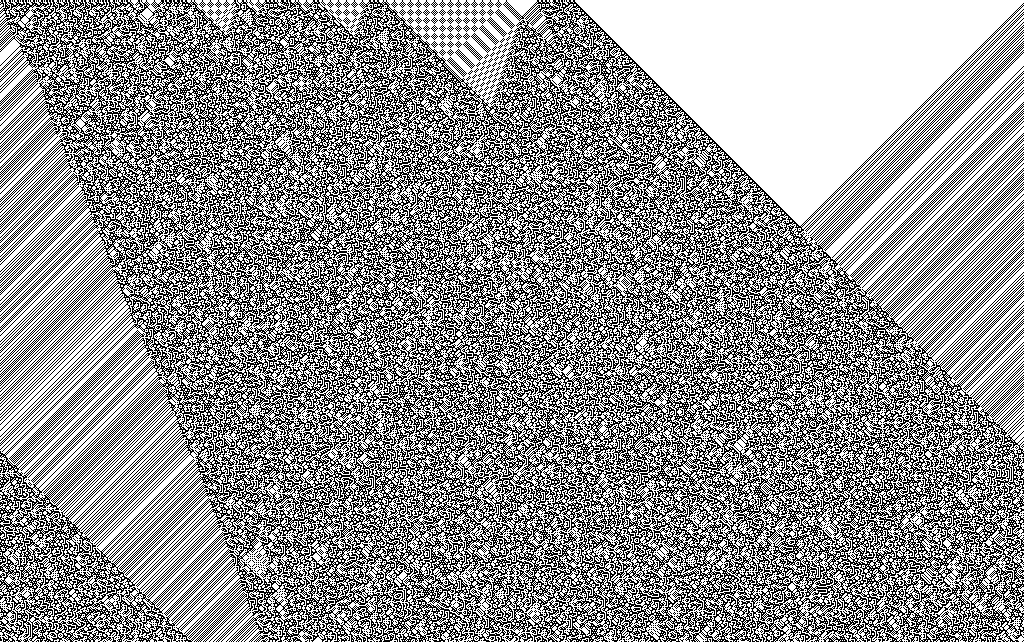

For illustration purposes, below is the kernel of the

the automata algorithm.