IT Outsourcer Gamed US H-1B Visa Lottery For Indian Workers Over Others

“It was very clear to me that my job was gone”

“There was preference given to employees from South Asia”

“I felt like an outsider, always”

“Cognizant is going to pay dearly one day”

“There’s a sense of betrayal”

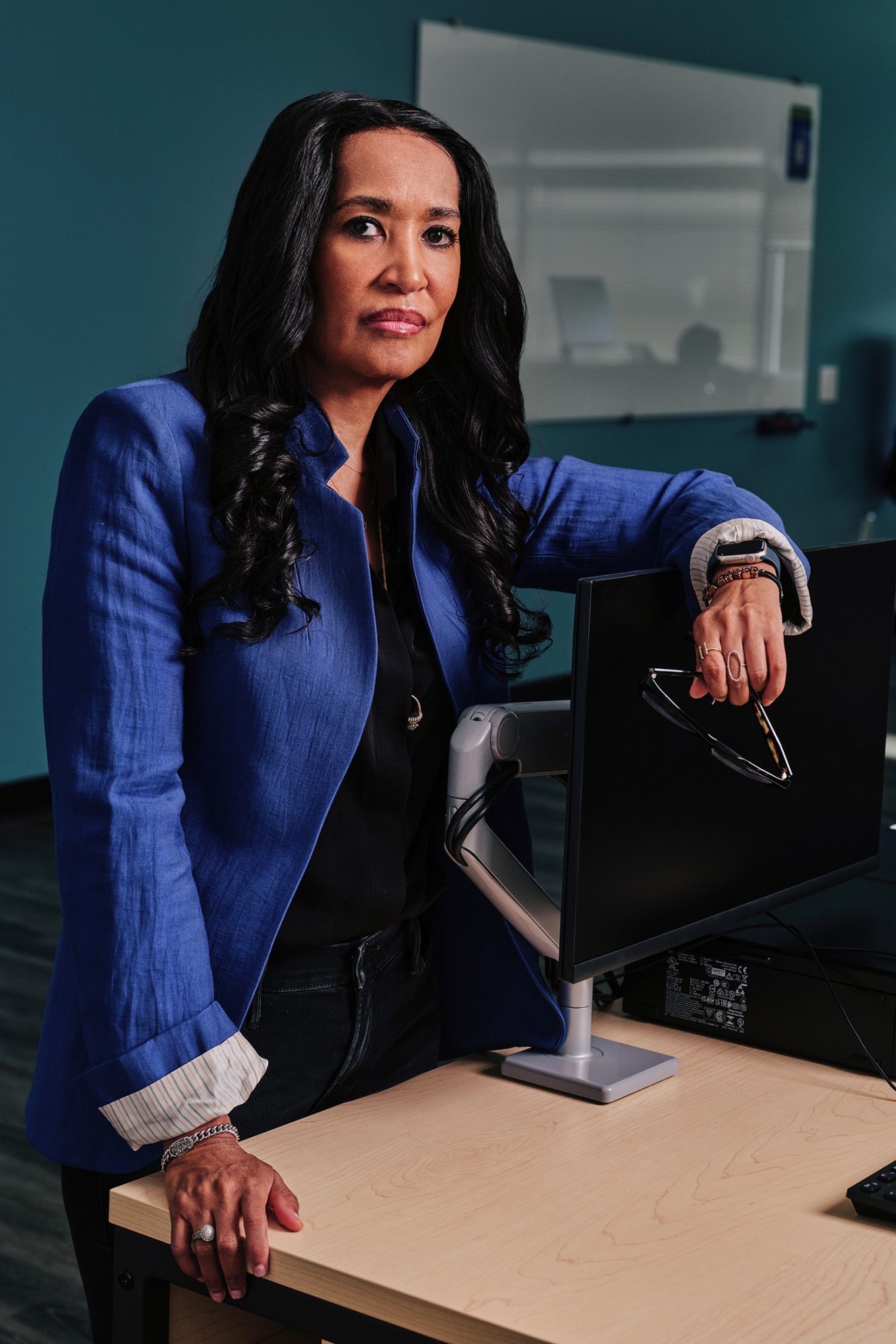

Six months into her job, Latreecia Folkes had launched a new project and received a letter of praise from her supervisor. And then, she says, she was told to train her replacement on the project, a worker from India. She balked at that but was replaced anyway.

Over the next two years, Folkes said, she was repeatedly denied opportunities for advancement as a project manager at Cognizant Technology Solutions Corp., one of the world’s largest information-technology outsourcing firms. She was offered chances to apply for roles that required her to relocate, but she couldn’t because her mother was ill. Over time, her relationship with the company grew strained, and Folkes said she knows why.

“I definitely knew it was because of me being an American, not being Indian, and also because I was Black,” she said in an interview. Folkes filed an internal discrimination complaint in 2017, three days before she was fired.

In October, a jury in a federal class-action lawsuit returned a verdict that found Cognizant intentionally discriminated against more than 2,000 non-Indian employees between 2013 and 2022. The verdict, which echoed a previously undisclosed finding from a 2020 US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission investigation, centered on discrimination claims based on race and national origin. Cognizant, based in Teaneck, New Jersey, was found to have preferred workers from India, most of whom joined the firm’s US workforce of about 32,000 using skilled-worker visas called H-1Bs.

Latreecia Folkes

Cognizant employment period:

2015–2017

Main role:

Project manager

The case is part of a wave of recent discrimination claims against IT outsourcing companies that underscore growing concerns that these firms have exploited a broken employment-visa system to secure a cheaper, more malleable workforce. In the process, US workers say they’ve been disadvantaged. The industry, which provides computer services to other companies, makes extensive use of H-1Bs; over the past decade and a half, no employer has obtained more of them than Cognizant, federal records show.

Cognizant spokesman Jeff DeMarrais said the company plans to appeal the verdict and disagrees with the EEOC finding. “Cognizant provides equal employment opportunities for all employees and does not tolerate discrimination in any form,” he said. He also said the company has sought fewer new visas over the past several years and said any apparent disparities in its hiring stem from a shortage of US tech workers. “Like many consulting firms and other technology companies in the US, Cognizant utilizes the H-1B visa program to fill positions it cannot fill with available US workers,” DeMarrais wrote in one of several emailed responses to questions from Bloomberg News.

Indeed, the H-1B program was designed to help US employers find specialized talent. But a decade’s worth of records from the US Department of Labor shows that outsourcing companies, including Cognizant, have used the visas mostly to fill lower-level positions, such as IT system analysts and administrators. Fewer than 20% of the 6,400 visa holders Cognizant has sponsored since 2020 had a master’s degree or higher, according to data from the US Citizenship and Immigration Services. At companies such as Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc., that figure is about 60%.

Outsourcers Hire Indian H-1Bs Without Advanced Degrees

Source: US Citizenship and Immigration Services data from 2020–2023

Meanwhile, US workers who say they’ve been treated unfairly are pushing back. Since December, at least 33 former US employees of Tata Consultancy Services Ltd, a Mumbai-based IT outsourcer, have filed complaints with the EEOC, alleging Tata fired them in favor of Indian visa workers. The company didn’t respond to requests for comment. Over the past five years, each of the five largest outsourcing companies has either settled, lost or is currently fighting a discrimination lawsuit. Yet, while this year’s US presidential campaign focused attention on undocumented immigrants and contested claims that they take jobs Americans want, the employment visa system has received far less attention.

In July, a Bloomberg News investigation revealed how outsourcing firms have overwhelmed the annual lottery for a limited number of new H-1B visas. While such companies are best known for serving American clients from India, they’ve also brought tens of thousands of Indian visa workers to the US. Using their vast overseas workforces – Cognizant employs more than 250,000 people in India – the companies submitted thousands of entries to secure a steady stream of visas for workers who, on average, had less educational attainment and received lower pay than other visa recipients, federal data show.

Now, internal documents and data that surfaced in the Cognizant lawsuit as well as interviews with more than a dozen former employees provide a rare view into how the push to hire visa workers at one outsourcer affected employees of different nationalities, races and ethnicities.

A Bloomberg analysis of Cognizant’s internal data found that from 2013 through 2020:

- About two-thirds of the firm’s US-based employees were from India.

- American workers were twice as likely to have their employment “terminated” – by resignation or dismissal – as were their counterparts on visas.

- For Black and Hispanic or Latino workers, the annual rates of such terminations were about three times higher than for Indian nationals.

Indian Employees Had Much Lower Attrition Rates

The gap in terminations by resignation or dismissal increased for Black and Hispanic or Latino workers

Source: Cognizant US human resources data, 2015 through 2020

Note: Bloomberg’s analysis excluded 2013 because only three months of data were available that year. It also excluded 2014 because of an abnormally high rate for Hispanic or Latino workers.

Cognizant’s DeMarrais said Bloomberg’s analysis of terminations was flawed because it didn’t include visa workers who left the company’s US operations “by choosing to return to their home country.” The company’s lawyers raised similar arguments in pretrial motions, but the judge ruled that Cognizant had refused to provide information about “what actually happened” to such employees — that is, whether their employment ended or not — and forbade Cognizant from presenting the issue to the jury. DeMarrais declined to say whether those employees continued to work for the company after leaving the US.

DeMarrais said the company’s current US workforce is 60% Asian, including Indian workers. According to 2023 data the company submitted to the EEOC, 70% of Cognizant’s professional and managerial staff reporting to its operational headquarters in Texas identified as Asian. The 24,600 workers included in the data represent more than three-fourths of the company’s total US workforce. In 2022, about 18% of high tech workers nationwide identified as Asian, the EEOC reported earlier this year.

Last year, Cognizant received about 2,000 new H-1B visas, down from a peak of 16,000 in 2012 when it was staffing up its US operations after the Great Recession. DeMarrais told Bloomberg that recently, the company has sought fewer new H-1Bs than other outsourcing firms and said it was unfair to focus on his firm. Since 2009, Cognizant has received over 52,000 new H-1Bs, a higher total than any other company.

Top Users Since 2009

Many designated as ‘H-1B-dependent’

- H-1B-dependent

- Not H-1B-dependent

Sources: US Citizenship and Immigration Services, US Department of Labor

Former employees say Cognizant’s use of Indian workers stems from a strategy to reduce labor costs. DeMarrais said that’s not the case. Still, Cognizant has seen recent savings from its immigrant workers in the US: Federal wage data shows that while the median inflation-adjusted pay of the broader IT industry has held flat since 2020, for Cognizant’s H-1B workers, it fell by 20%. Cognizant’s most recent annual report said any legislation that would require higher pay for visa workers would be one of several “risk factors” facing the company.

Cognizant’s Median Pay Lagged Other Employers

Cognizant paid its H-1B employees less in recent years while the computer systems industry remained relatively flat

- Median annual salary by category

- Cognizant H-1B workers

- H-1B workers across all employers

- Industry-wide regardless of visa status

Sources: US Citizenship and Immigration Services and US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Note: Salaries adjusted to October 2023 dollars. Industrywide figures based on the North American Industry Classification System code 5415 for computer systems design and related services.

“Cognizant complies with federal laws regarding pay for visa workers,” DeMarrais said, and it “disagrees that any financial incentive exists to hire visa workers.” He added that many employees are assigned to sites away from major cities, where wages are typically lower. DeMarrais declined to provide geographic details, but internal company data from 2013 to 2020 show that 70% of Cognizant’s US employees worked in the top 20 most populous metropolitan areas, including New York, Phoenix and Dallas-Fort Worth.

In interviews, former employees said there’s another reason Cognizant prefers visa workers: They’re more willing to accept inconvenient or less-favorable assignments. Because their visas are tied to specific employers, H-1B workers face obstacles in the US job market. When they seek new positions, they must persuade new employers to take on the expense and trouble of transferring their visas. That can make them more likely to accept hardships from current employers, such as transfers to new worksites.

DeMarrais said repeatedly that Cognizant does not favor H-1B workers over US citizens. But he indicated that the company does value employees’ willingness to move around. The firm’s “decisions about who to hire and promote” are based on several factors, DeMarrais said, including clients’ needs and candidates’ credentials, experience and “willingness to relocate for projects as needed.”

Critics of the H-1B program say employers who depend on visa workers can gain unfair advantages in the workplace – over immigrants and US workers alike.

“It’s a business model that allows for exploitation,” said Maria L. Ontiveros, a professor emeritus at the University of San Francisco School of Law. “If you’re exploiting immigrants, it inevitably makes it harder for American workers. It rips up the floor for decent working conditions for everyone.”

An ‘H-1B-Dependent’ Model

Founded in 1994 as an Indian subsidiary of Dun & Bradstreet Holdings Inc., Cognizant moved its headquarters to the US in 1997, though more than 70% of its 340,000 employees are still in India. Its outsourcing model took off during the Y2K scare. Government and business leaders feared a collapse of global financial markets and communication systems because some computer programs weren’t prepared for the calendar to change to 2000. They needed programmers fast, but only for a one-off project.

No software-induced doomsday came to pass, but the IT outsourcing industry bloomed in the new millennium to satiate corporate thirst for cost-cutting. While moving back-office IT functions to India produced large savings, outsourcing companies also needed client-facing workers in the US. To fill those roles, they turned repeatedly to the US visa system, especially H-1Bs. Cognizant, which has a market capitalization of about $40 billion, generated nearly three-fourths of its revenue from North America in 2023, according to its most recent annual report.

Federal law caps the number of H-1Bs at around 85,000 a year, a limit that policymakers haven’t changed since 2005. Because demand far outstrips that supply, the USCIS holds an annual lottery to determine who can apply. To enter, applicants must be sponsored by their prospective employer, and employers must have a bona fide US job opening for each entry.

Former Cognizant executive Jean-Claude Franchitti, who worked there from 2007 to 2016, said he was shocked when he saw how the company sought some of its H-1Bs. As an assistant vice president in the firm’s Global Technology Office, Franchitti said he was asked to sign hundreds of letters attesting to federal officials that Cognizant’s Indian employees needed visas to work on assignments under him. Yet most of those assignments never existed, he testified during the discrimination trial in September. Only three of the letters he signed were for people who actually worked under him, Franchitti said.

Jean-Claude Franchitti

Cognizant employment period:

2007–2016

Main role:

Assistant Vice President, Global Technology Office

“The projects didn’t exist and none of those employees came to report to me ever,” he testified. He said he reported concerns about the visa applications and what he called discrimination against his non-Indian team members to human resources in April 2016. Three months later, he was fired.

DeMarrais disputed Franchitti’s allegations, pointing out that the former Cognizant executive is not an immigration attorney. He didn’t respond to a question about why the company dismissed Franchitti. The USCIS did not respond to questions about Cognizant’s visa practices.

An email sent to Franchitti by a member of Cognizant’s operations team in 2016 tends to support the former executive’s account. Submitted as evidence during the trial, it said that the company routinely applied “proactively” for workers’ visas, before actual work materialized. Asked about the email, DeMarrais said: “Cognizant complies with federal laws and regulations regarding visa applications.”

Another trial document, a 2016 internal Cognizant presentation, showed that 40% of the company’s H-1B visa holders remained in India for six months after being approved. At the time, Cognizant had accumulated more than 4,000 such “travel ready resources” offshore, the presentation said.

DeMarrais said the company “does not seek visas for the purpose of stockpiling them.” There can be various good reasons why H-1B holders wouldn’t leave India immediately for the US, he said: Some projects might take longer than expected; clients might change plans; workers might decide against moving to the US. He declined to provide any statistics on how many Cognizant workers with H-1Bs are currently in India.

But several former Cognizant executives told Bloomberg the company has had a large pool of H-1B visa holders in India that it looks to first when filing US job openings. Most of them asked that their names not be used, saying they didn’t want to damage their relations with Cognizant.

Sonya McLaughlin spent a decade as a director of US corporate talent acquisition at Cognizant until she was laid off in June. Her 10-member team’s role was to recruit job candidates from the US labor market. The company systematically prioritized transferring workers from India over hiring local workers, limiting her team’s effectiveness, she said in an interview.

Cognizant pledged to make more US hires, but that was “all smoke and mirrors,” said McLaughlin, who was not part of the federal lawsuit. “The entire business model is built on the back of cheap Indian labor. The people who are on visas are the people Cognizant wants.”

Cognizant Boosted Diversity, But Mostly at Lower Levels

Indian workers dominated professional IT roles while American hires tended to fill lower-paid jobs such as content moderation.

- Indian nationals

- Non-Indian Asian

- White

- Black

- Hispanic or Latino

- Other

Source: Cognizant US human resources data, from 2013 through November 2020

Note: Excludes temporary contractors and executive-level jobs above Assistant Vice President. Read our full methodology for more information.

DeMarrais disputed that characterization. When new roles open in the US, he said, the company first seeks to fill them with current employees who are between assignments, a status Cognizant refers to as on “the bench.” If that doesn’t work, the company seeks “to pursue talent within the US labor market before identifying employees in India who may be able to travel and fill the role.”

Former employees said that at Cognizant, being on the bench can be precarious. Those whose assignments end typically have less than two months to find new ones somewhere in Cognizant’s nationwide service area before losing their jobs, they said. US workers said they received little support and were often asked to relocate to different states or they would be fired.

Latreecia Folkes was put on the bench twice during her two years at Cognizant, according to the company’s internal data. She spent less than a month there in late 2016 before finding a position in South Carolina, which required her to fly back and forth from her home in Atlanta. She went on the bench again in March 2017. She said she spent a month trying to get on a new project. After being passed up for multiple positions, she said she was offered one that required her to relocate to Washington, DC. That’s when she filed an internal discrimination complaint, alleging she was being pushed out of the company.

“You get on the bench,” and can spend several weeks there, said Folkes, a US Army veteran now pursuing her PhD in computer science while teaching at a technical college. “In that time, they said they would get you a role for you to apply to internally. And I applied like a dog. I applied, I applied, I applied, almost begging.”

Since the creation of H-1B visas in 1990, policymakers have struggled to find effective ways to regulate them. Reforms proposed in 2015 would have prohibited large companies with more than half of their workers on the visas from obtaining new ones. The bill didn’t pass, but the prospect of a ban alarmed Cognizant executives. In a December 2016 internal presentation, the firm’s chief operating officer at the time proposed a half-dozen “levers” for reducing its ratio of visa-workers, such as applying for more green cards, automating job functions and moving positions to Canada. Hiring more Americans was the last option – one that “may reduce margin,” the presentation said.

Rules that have been adopted aren’t always effective. The US Department of Labor classifies Cognizant as an “H-1B-dependent” employer, which means more than 15% of its workers have the visas. Companies with that designation are required to attest that they’re not taking jobs from US workers – but only if they pay their visa workers less than $60,000 a year, a threshold that hasn’t been increased in two decades. Consequently, none of the outsourcing firms that have been deemed “H-1B-dependent” – Wipro Ltd, Infosys Ltd, Tata, Cognizant and HCL Technologies Ltd – is required to make the attestations.

Franchitti, the former executive, took his case to the EEOC, the federal agency that investigates complaints of job discrimination. Four other former Cognizant employees did likewise. In 2020, the agency wrapped up its probe with a finding that Cognizant discriminated against a “nationwide class of non-Indian employees on the basis of race and national origin.” But that finding had little impact, partly because federal law forbids the EEOC from making its findings public or imposing fines, except when a company fails to post required notices.

So Franchitti and others decided to go to court.

When Christy Palmer joined Cognizant in 2013, she relished the opportunity to work at a multinational corporation that served some of the most iconic US companies. It wasn’t long before she began to feel out of place, uncomfortable and, at times, intimidated, she said during court proceedings and interviews with Bloomberg. At a client meeting in 2015, a Cognizant director was struggling to respond to questions about a report Palmer had written, so she tried to step in with an answer. According to Palmer and another person present, the director cut her off, swearing loudly at her to shut up.

Palmer said that the incident was the culmination of years of alienation she experienced as a project manager at Cognizant and that much of the ill treatment she received stemmed from the fact that she’s not Indian. As one of only two non-Indian workers and the only woman on her 15-person team, Palmer said she was routinely excluded from important team meetings.

Christy Palmer

Cognizant employment period:

2013–2016

Main roles:

Project manager, IT infrastructure architect

Testifying during the federal trial, she recalled a day when she watched her team gather in a glass office without her, even though she was part of the project they were discussing. She said she was also shut out of social gatherings, including lunches and after-work events. Once, when she asked why she wasn’t invited, she said, a colleague told her it was because she didn’t like Indian food. “But I do like Indian food!” Palmer protested.

After producing important work for clients, she said at trial, she was often replaced on projects by less-experienced and lower-paid H-1B workers. Once, she was asked to train a replacement on a particular software she’d mastered, Palmer said. “I don’t care where you come from,” she said in an interview. “But don’t replace me with someone who has less experience.”

Being replaced on assignments, shut out of meetings and blocked from social events stymied her career at Cognizant, Palmer alleged in the federal lawsuit. Fed up, she left the company in 2016.

Others told Bloomberg similar stories. A Black manager said he was brought into multiple projects to help win customers’ business, but each time executives later replaced him with Indian employees who he said received credit for securing the accounts. A global executive who managed over 1,000 employees said the company’s preference for Indian H-1B workers is intrinsic to its outsourcing business model because they are almost always the cheapest labor option. Both worked at the company in the past three years and spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing career repercussions.

Palmer, Franchitti and others who left Cognizant found a Washington DC law firm, Kotchen & Low LLP, that was specializing in class-action lawsuits against outsourcing companies. Daniel Kotchen, a former antitrust lawyer at the Federal Trade Commission, set up the firm with his partner, Daniel Low, in 2008. Some of their earliest clients were H-1B workers who were “promised jobs that didn’t exist and put in horrible conditions,” Kotchen said in an interview.

Kotchen filed a class-action discrimination case against Cognizant in September 2017. That same month, Cognizant hired a new senior director of equal employment opportunity, Abby Israel. Her job was to ensure the company didn’t discriminate. It wasn’t long before her name cropped up in Kotchen’s pretrial discovery. She later testified at trial that she found rampant discrimination at Cognizant and tried to address it but was ignored.

Abby Israel

Cognizant employment period:

2017–2020

Main role:

Senior director of equal employment opportunity

Israel had two decades of experience as an EEO officer at large US companies, including PepsiCo Inc., Emerson Electric Co. and Deloitte LLP before joining Cognizant. She said in court that Cognizant executives didn’t tell her about the EEOC investigation that was under way when she joined the firm, even though she was responsible for reporting diversity data to the agency.

In 2018, Israel’s team produced an internal report that found large racial disparities in rates of “involuntary terminations” at Cognizant over the first eight months of the year. Black employees were let go at a rate 23 times that of Asian workers, the data showed. For Hispanic or Latino employees, the rate was 16 times the rate of their Asian counterparts. For White workers, it was eight times as high. (The Asian workers were overwhelmingly from India and were working on visas, according to the report.) Israel told the jury that those were some of the most extreme racial disparities she’d ever seen. She also said that when she reached out to Cognizant’s hiring managers with those findings, her supervisor told her to stop sharing the data beyond HR leaders.

DeMarrais said Israel was given that instruction “due to confidentiality concerns.” The disparities in her report resulted from the shutdown of several substantial projects at the time, he said, and they’re “not representative of Cognizant’s practices.” He noted the report also showed that during the period, Cognizant hired more non-Indian employees than those who left the company, and it hired more non-Indian workers than Indian workers.

In 2020, a Cognizant recruiting executive referred to what he saw as the company’s discriminatory practices in a text conversation with Israel that was submitted as evidence during the trial: “An open secret: we hired H1s for the longest because they were cheaper labor that would relocate anywhere.”

“Yeah see … that’s race discrimination,” responded Israel, who left Cognizant four months later. “Cognizant is going to pay dearly one day.” Plaintiffs’ attorneys say they plan to seek damages for the class members that could reach into hundreds of millions of dollars; however, that will require a separate trial, and the company will contest any penalties.

Cognizant has pushed back against the lawsuit by filing a countersuit against Franchitti and two other named plaintiffs, alleging that they breached corporate confidentiality agreements. The case is ongoing. A federal official said that type of lawsuit may violate EEOC rules.

In an email, EEOC spokesman Victor Chen said the agency doesn’t comment on specific litigation but that “filing a civil action against an employee who has engaged in a protected activity (for example, by filing a discrimination lawsuit) can be a form of retaliation.”

Cognizant made headlines earlier this year when about 40 of its employees assigned to work for Google LLC’s YouTube Music in Austin, Texas, sought to unionize so that they could negotiate for wage increases and better working conditions.

The workers said they scored important victories when the National Labor Relations Board ruled that Cognizant and Google were co-employers and had violated labor laws by refusing to bargain with the unionizers – decisions that both companies have appealed. But the organizers encountered a setback during an appearance before the Austin City Council in February.

There, as the council considered a resolution urging Google to recognize the union, one of the workers stepped up to the podium. “Not to interrupt,” Katie-Marie Marschner said. “But they just laid us all off.”

Cognizant said at the time that the workers had not been fired but that its contract to work for YouTube Music had simply expired. DeMarrais told Bloomberg the workers “were moved to our bench,” where he said they received full pay and benefits for eight weeks and were given the opportunity to retrain to move to a new project. He said the workers rejected or ignored all such “offers to continue their employment.” He didn’t respond to questions about where the opportunities were located or what they paid.

Today, all of those workers have since left Cognizant, Marschner told Bloomberg. But YouTube Music has not. The streaming service has continued to use the outsourcing company in the months since the city council meeting, Google told Bloomberg News. (Google also said it had no role in determining the former workers’ employment status.) Asked about its continued work for YouTube Music, DeMarrais said Cognizant doesn’t discuss specific client work.

Union leader Jack Benedict said that at the time, the Austin workers were told to update their resumes. While some may have been contacted about new projects, he said, he never was and “not a single one of us” got hired for any of the projects.

Jack Benedict

Cognizant employment period:

2022–2024

Main role:

Music generalist

Benedict and former colleagues said they had trained at least 10 employees stationed in India in the year or so before they left Cognizant, raising fears among the group that they’d be replaced by Indian workers.

DeMarrais said the suggestion that workers in Austin trained their replacements wasn’t accurate and that the majority of the Austin employees were “musicians” whose “job was to curate musical play lists.” Still, about a month before Benedict and others say they were let go, a Cognizant employee in India published a “Hiring Alert” on LinkedIn for musicians, music producers and music journalists. In fact, Benedict said he had trained one of the Indian-based workers who posted about the jobs.

In an interview, Benedict said it’s clear to him that the workers were replaced. “Google needed the work and still needs the work to be done,” he said, noting the Cognizant team in Austin “had great quality and great performance.”

However, he said, “there are people overseas that [Cognizant] can work longer, pay less and don’t have the legal infrastructure to … make trouble like we were doing.”

(Editor’s note: During the reporting of this story, a representative for Cognizant repeatedly asked Bloomberg to disclose its own H-1B data. Since 2009, when the US government began disclosing the numbers, Bloomberg has successfully sponsored 3,082 new H-1B visa petitions, according to the most recent data from the US Citizenship and Immigration Services.)